Since Uber went public in May 2019, journalists and analysts have sharpened their skepticism regarding the viability of the company’s sweeping ambition and future-reliant success. A 23 percent drop in the company’s stock shares (as of August 19) and its second quarter loss of $5 billion, mostly due to stock-based compensation, cause investors to wonder what profitability will look like for the international mobility-on-demand company.

While second quarter earnings weren’t as palatable as investors would’ve liked, Kent Schofield, Uber’s Head of Investor Relations, said during the earnings conference call that the statements would be “forward-looking” and they would use terms such as “believe, expect, intend and may.” One aspirational statement followed from CEO Dara Khosrowshahi in response to a question on profitability – “We’re very confident that this company at maturity can be cash flow-positive, and the team is focused on being able to drive big-time growth at the top line while getting more efficient on all parts of the business.”

Ride-sharing is projected to be a $220 billion industry by 2025 (it was $61.3 billion in 2018). Uber predicates its long-haul success on the assumption that car-buying, especially in the millennial and Gen Z generations, will lose desirability, especially as post-grads move to large metropolitan areas where car-ownership is tedious, expensive and environmentally problematic. “When we look at the ride-sharing category, our top competitor in this category is car ownership and other ways of getting around. And when I look at how we are faring against car ownership, we’re faring very well,” Khosrowshahi said.

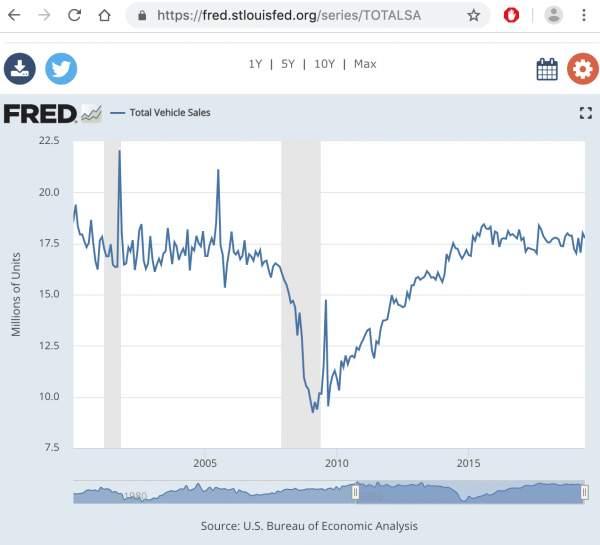

While millennials were slow to buy cars and were early adopters of Uber’s convenient and environmentally friendly services, time and hindsight reveals (in the chart below) that the millennial hesitation to buy cars may have been more about Great Recession insecurity than progressive thinking.

Perhaps Khosrowshahi’s confidence rests on Uber’s new Volvo XC90 SUV self-driving car, tested with new fail-safes and due on the roads in 2020. This thorough testing comes a year and a half after Elaine Herzberg walked in front of a self-driving Uber in Tempe, Arizona and was killed.

It may take a significant amount of time for autonomous cars to replace the desired autonomy of car ownership. The growth of on-demand mobility could be a cause of teenagers delaying their driver’s license, as well as city-dwellers continuing to shirk car-owning responsibilities in lieu of Uber, Lyft and public transportation. But what about middle America? Rural and suburban Americans remain steadfast car-owners and could be the last and most-stubborn frontier for Khosrowshahi to achieve her vision of a car-sharing economy.

But Uber’s sights extend far past the United States. The company has moved into over 60 countries and is continuing to grow its user base in food-delivery (Uber Eats), freight brokering (Uber Freight), patient transport (Uber Heath), customer loyalty products (Uber Rewards) and luxury riding (Uber Comfort). To the consumer, Lyft and Uber are close rivals for ride-hailing, but Uber’s wider international reach and greater differentiation of services relies on the long-game and faith of investors, as it attempts to dramatically reshape the consumer relationship with transportation.