This morning, a super-team of Stifel equities analysts covering all modes of transportation and categories of logistics companies came together like Voltron and issued a research report detailing their view of the risk to transport stocks posed by tariffs and a potential trade war. David Ross (trucking), Bruce Chan (global logistics), Mike Baudendistel (railroads), Ben Nolan (ocean shipping), and Joe DeNardi (airlines) presented their perspectives on the origins, purpose, and likely outcomes of the Trump administration’s pivot toward protectionism.

Even a large-scale trade war is unlikely to reshore large volumes of industrial production back to the United States because the country is already experiencing a widespread shortage of blue-collar labor (it manifests itself in the trucking industry as a driver and maintenance technician shortage), Stifel said. And shippers will wait to see how severe, and more importantly how permanent the tariffs will be before undergoing costly adjustments of their supply chains. At this point, according to Stifel, the most likely outcome is that shippers moving goods with inelastic demand will pass on rising costs in the form of higher consumer prices, while other manufacturers will be forced to eat the costs. Thus, the main risks to the transport sector from a trade war are twofold: rising consumer prices leading to inflation and suppressed demand, and compressed corporate profit margins.

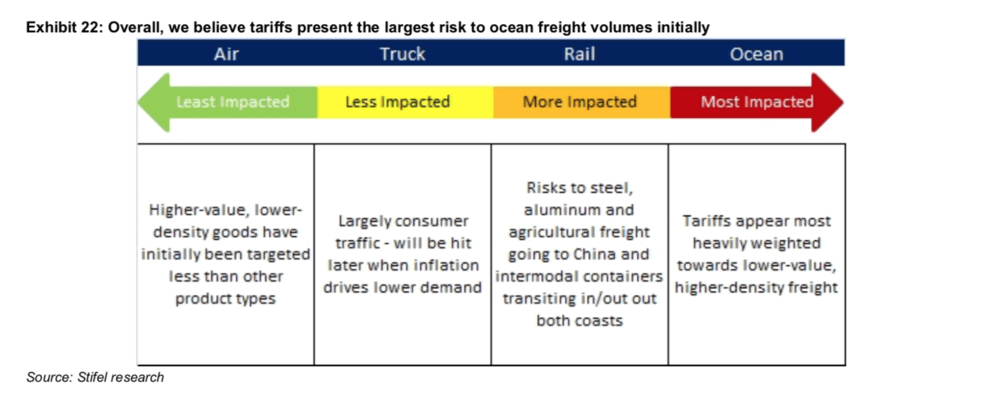

Stifel believes the mode most exposed to trade war risk is maritime shipping, particularly dry bulk haulers carrying commodities like steel, iron ore, coal, bauxite, and grains that have been specifically targeted by tariffs. Nolan noted that every ton of steel production re-shored to the United States implies a reduction of imported iron ore by two tons and imported metallurgical coal by one ton. “Tariffs appear most heavily weighted towards lower-value, higher-density freight,” Stifel wrote. Container shipping would only be modestly affected, Nolan said, while tanker vessels carrying petroleum products are not at risk.

Railroads are slightly less exposed trade war risk than maritime shipping, but more threatened than trucking or air cargo. Baudendistel sees the rails’ risk primarily in their steel, aluminum, and agricultural freight headed to China, as well as intermodal containers going through the ports.

“While the rails handle goods that are both imported and exported, the freight that is exported, such as export coal and export grain, are commodities that are competitive in a global marketplace with other producers around the world (e.g., competitive with coal mines in Australia or grain producers in Russia) and are sensitive to competing prices and exchange rates. In a full-out trade war, retaliatory tariffs could make coal and grain exported from the U.S. uncompetitive or less competitive,” Baudendistel wrote.

JB Hunt and HUB Group’s intermodal exposure make them most at risk among trucking companies. The downside for other trucking carriers is more diffused and indirect: if higher prices suppress consumer demand, truckload volumes will suffer, carrier’s pricing power will dissipate, asset utilization will fall apart, and operating ratios will soar.

“These tariffs are not expected to change the current healthy pricing environment for [truckload] carriers,” Ross wrote, “as it shouldn’t immediately reduce freight volumes (port movements represent a small fraction of overall truck moves, especially for the public carriers), and it certainly won’t create more qualified truck drivers. Most of our coverage is dry van truckload with heavy consumer exposure. Were tariffs to drive the price of consumer goods higher over time, it would lower discretionary income, assuming wages weren’t growing as fast as inflation. The biggest concern here and for the broader market and economy is the negative impact of sustained higher tariffs on consumer (and industrial) spending.”

Bruce Chan wrote that global freight forwarders and logistics providers could see an increase in volumes due to tariffs, as shippers lean on them to provide access to capacity across modes, to help redesign and manage supply chains to offset the cost of tariffs, and to navigate complex regulatory and customs frameworks. “So far, though, most carriers and transportation service providers cite little change to volumes and business activity, either positive or negative,” wrote Chan. “But there are a number of long-term implications that are all almost certainly negative, in our view, for the global freight forwarders. The most obvious of these is a reduction in cross-border trade volumes for both air and ocean activity.”

Stay up-to-date with the latest commentary and insights on FreightTech and the impact to the markets by subscribing.