Trump’s Mexico tariffs set a dangerous precedent for policy, with potentially huge effects

Yesterday, President Trump announced plans to enact new tariffs on all goods imported from Mexico, with the intent of addressing illegal immigration across the U.S.-Mexico border. Imports will be subject to a 5 percent tariff beginning on June 10, 2019 and will gradually escalate to 25 percent by October 1 if a resolution on immigration is not reached.

In doing so, President Trump will reverse 25 years of open trade relations with Mexico, starting back in 1994 with the North American Free Trade Agreement. This type of move continues the Administration’s push away from free trade arrangements, which began early last year with tariffs on steel and aluminum imports. It also raises some concerns that Mexico may retaliate and place its own tariffs on goods imported from the U.S., though Mexico’s president Andrés Manuel López Obrador has thus far insisted that he only wants to seek a resolution with the U.S.

In many ways, the impact of these new tariffs will be similar to previous tariffs, with each wave causing disruptions in targeted industries and in overall economic growth. However, the details of the U.S. relationship with Mexico and the motivation for tariffs on these imports presents some unique challenges to the outlook.

On U.S.-Mexico trade and the complications with tariffs on Mexico

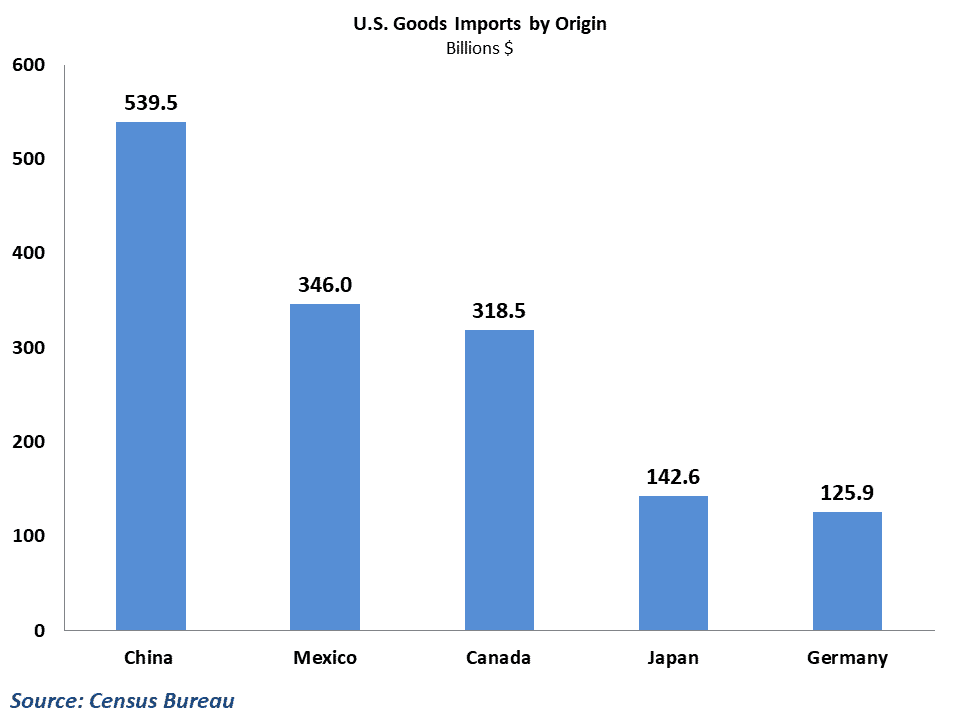

Historically, the U.S. has been one of Mexico’s largest trading partners; the nearly $350 billion that the U.S. imports each year from Mexico ranks only behind China in terms of top import origins, and the $265 billion it exports to Mexico is second to Canada for export destinations. Motor vehicles and parts make up the largest category of imports from Mexico, making up over one-third of the total, with computers and electronics, industrial equipment and agricultural products also in high demand from U.S. consumers and businesses.

The most direct effect of these newly announced tariffs is that the cost of importing these goods will now begin to rise, and businesses will have to decide whether to bear the burden of these costs themselves or pass them on to end consumers in the form of higher prices for finished products. In this sense, this new set of tariffs operates similarly to the tariffs on goods coming from China or the broad tariffs on steel and aluminum that were implemented in 2018.

The hitch with Mexico, however, is that much of the trade that crosses borders is trade that occurs within a single company’s supply chain. Because of Mexico’s close proximity to the U.S. and the free trade environment that has persisted for a quarter of a century, U.S. companies frequently open factories in Mexico to produce components, then move parts across the border during the production process. Torsten Slok, the chief economist and managing director at Deutsche Bank Securities, notes that two-thirds of all imports from Mexico is related-party trade, which is trade within firms with at least 10 percent of the ownership of the trading partner.

What this means is that these tariffs on imports from Mexico are going to predominately hurt U.S. companies. This is particularly true in the auto industry, as parts like engines and transmissions are imported from Mexico in order to complete production and sell in the U.S. As these tariffs escalate, it will have a crippling effect on the already struggling auto and truck manufacturing sector, particularly in the short-term when businesses are unable to adjust their supply chains. Over time, firms may begin to rethink how they manufacture and assemble goods, and will likely settle on more domestic manufacturing within the U.S., albeit at a higher cost to producers and consumers.

A dangerous precedent, spillover effects and the impact on the macroeconomy

Despite the possibility that companies may begin to relocate back to the U.S. over the long-term in response to these tariffs, officials from the Trump Administration have been insistent that improving domestic manufacturing conditions is not the end goal. Traditionally, tariffs have been used at various times to resolve a number of different issues in foreign trade, either protecting domestic industries as in the case of the steel and aluminum tariffs, or attempting to correct perceived bad behavior as in the case with China.

Tariffs on Mexico’s goods represent a significant policy shift in this regard. The stated target for removing these tariffs hinges on illegal immigration, and as such, this move represents an attempt to use tariffs as a blunt tool to fix a foreign policy dispute with another nation.

Economic pressure has been used in the past by the U.S. to pressure foreign governments to act, but these moves typically take the form of sanctions. Sanctions require approval from Congress before they can be used on another nation, and are usually reserved for nations that have a contentious relationship with the U.S. President Trump has the ability to implement tariffs without the consent of Congress, and now appears to be willing to tie U.S. trade policy to some of his other political objectives.

This sets a dangerous precedent for the U.S. economy and vastly complicates the business investment decisions of companies. This is likely to cause a significant reduction in business confidence, even in areas that aren’t directly involved in importing from Mexico, and suggests that any global component of a supply chain could be targeted if the U.S. enters into a dispute for any reason with the involved country. In addition, the tariffs on Mexico came with little warning, and businesses have only a short period of time to adjust before they take effect.

These types of policy moves introduce an incredible amount of uncertainty into the business environment. Designing and implementing complex global supply chains is a lengthy and expensive process, and once they are in place, it can be difficult to adjust to sudden swings in policy. As a result, businesses may pull back by either suspending or calling off current investment plans until this situation works itself out.

As a result, there are likely to be a significant amount of indirect effects from this policy on overall macroeconomic activity, particularly on the goods side of the economy. While much of the tariffs in 2018 came during a time when the economy was performing well and were easier to absorb, these current tariffs come at the wrong time for the U.S. – and for that matter the global – economy. While GDP growth was strong during the first quarter, goods activity in manufacturing, trade and retail either slowed significantly or declined outright at the start of the year in the U.S. Global data has been just as poor, with manufacturing and trade numbers across many of the world’s largest economies struggling. While it is not clear that these tariffs will stay in place and there are legal questions about the ability of the President to use tariffs to achieve these immigration goals, the threat of what may come from this has become a significant risk to the outlook for the overall economy.