Shippers and carriers alike are exposed to spot market volatility

Commentary

FreightWaves staff members and writers often speak with freight brokers and third-party logistics providers (3PLs), from front-line salespeople and carrier reps to C-suite executives, in order to learn about the current state of the freight market, how brokerages are impacted, and to try to glean insights into what may be coming next. In recent conversations, we’ve come across an interesting slang term from our contacts in Chicago – some brokers refer to contract rates as ‘paper rates.’ Why?

There are at least three ways to interpret the ‘paper’ in ‘paper rates.’ The first is that the rates aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on, but that feels too harsh. The second could be that contract rates are ‘just what’s on paper,’ implying that they do not necessarily hold up in the real world. The third possible connotation is that ‘paper’ means something like ‘official’ or agreed-upon.

The second option is most likely – contract rates by no means guarantee that a shipper will find capacity at a certain price or that a carrier will receive a certain volume at that price. Contract rates are ‘paper rates’ because they are subject to change by market conditions – they’re only good for 12 months in theory, i.e., ‘on paper.’

A Tuesday afternoon telephone call with a freight brokerage executive based in Chicago clarified the term ‘paper rate.’

“It’s a negative term applied to contract rates that are no longer working for whatever reason,” the broker said. “They’re just good on paper.”

Many asset-based carriers and large 3PLs with contract business like to maintain the convenient fiction that contract rates are entirely separate from spot rates. Publicly traded truckload carriers may tell their investors, for instance, that they’re only 15 percent exposed to spot rates, meaning that only 15 percent of their trucks will pay current market rates and the other 85 percent of their volume will be handled according to stable, pre-negotiated rates.

But contract rates are not actually legally binding contracts. A shipper has no legal remedy if a carrier rejects a contracted load, and a carrier will not be compensated if a shipper does not tender the agreed-upon volumes.

Additionally, shippers’ routing guides further destabilize the idea of firm contract rates. A carrier may say that it is confident in securing five percent increases in contracted rates, but if that rate increase pushes the carrier further down the shipper’s routing guide, say to the third position, then the carrier will receive far less freight. In current market conditions, very few loads are being rejected and more than 90 percent are being handled by the primary carrier, which places downward pressure on contract rates.

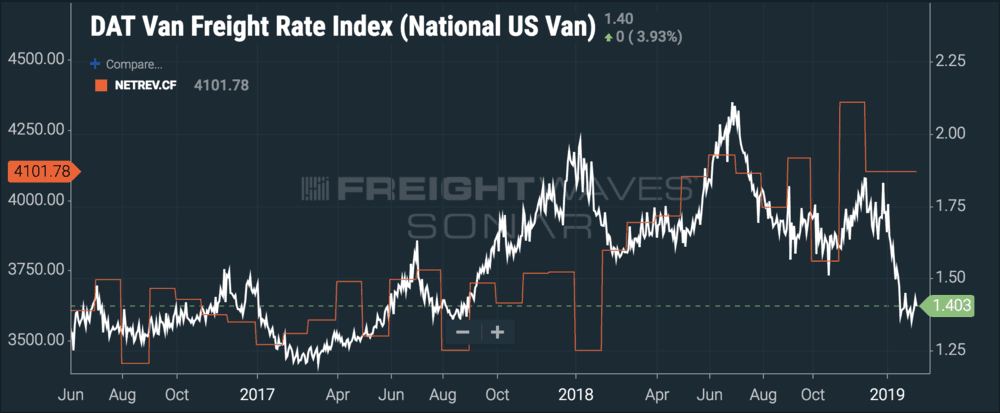

The SONAR chart below illustrates how exposed typical truckload carriers are to spot market volatility, even if the majority of their volume is priced according to contract – or paper – rates. The white line tracks the national average DAT spot rates for dry vans (DATVF.VNU), a daily number, and the orange line represents net revenue per truck per week for company fleets (not leased owner-operators), reported as a monthly average (NETREV.CF). The revenue per truck per week data is generated by the Truckload Carriers Association’s Profitability Program.

Clearly, truckload carrier revenues are exposed to spot market volatility despite those carriers’ preference for ‘contract freight.’ When spot rates go up, revenue per truck goes up, and when spot rates fall, revenue per truck falls. Because revenue per truck is a monthly number in the SONAR chart, it’s hard to tell exactly how sensitive revenues are to spot rates, but a quick glance at the first part of 2018 and even November 2018 shows how tightly correlated the two metrics are.

The tight correlation between spot rates and revenue per truck is the data behind brokers’ gut feeling that sometimes contract rates are only good on paper. When the market heats up, contract rates become ‘paper rates’ and tender rejections spike above 25 percent (OTRI.USA), as they did in late June 2018. In a soft market, small- and medium-sized shippers will be tempted to put their loads into the spot market, taking advantage of lower-priced capacity. Large shippers are less likely to skip their routing guides entirely because of the labor-intensive process of covering high spot volumes. Finally, many shippers and carriers have an understanding that ‘contract rates’ can be mutually renegotiated every quarter or so, depending on market volatility, further blurring the line between contract and spot.

It turns out that a negative, somewhat cheeky slang term that freight brokers use for obsolete contract rates can actually reveal a great deal about how there is no fine line between contract and spot pricing because both are subject to the same interlocking market pressures.