A metal mined in the DRC and refined in China poses the biggest supply chain risk to electric vehicles

It’s in the smart phone in your pocket, in the turbine blades of the airplane you fly in, and it’s one of the main components of the batteries used by electric cars. Cobalt—the primary ingredient in lithium ion battery cathodes, which are really made up of lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2)—is a hard, lustrous, silver-gray metal formed by supernovas billions of years ago, and does not naturally occur in its pure form on Earth. The main source of the element today is as a by-product of copper and nickel mining, especially in the Central African Copperbelt, which produces more than 50% of the global supply of cobalt.

FreightWaves has reported on the soaring demand for metals like copper and aluminum generated by the growing electric vehicle industry, as well as some of the environmental issues associated with production of those metals—for example, the smelting of aluminum for EVs is actually making China’s smog problem worse. Today we’re going to take a look at cobalt, a major component of the lithium ion batteries that power all kinds of devices, from laptops to electric cars. There are really two issues with the widespread use of cobalt in batteries: there isn’t nearly enough cobalt being mined to meet the production goals of EV companies like Tesla and the cobalt we do have is being mined by child slaves in warlord-controlled regions of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

We’ll take up the supply and demand issue first, and then turn to the ethics of cobalt production.

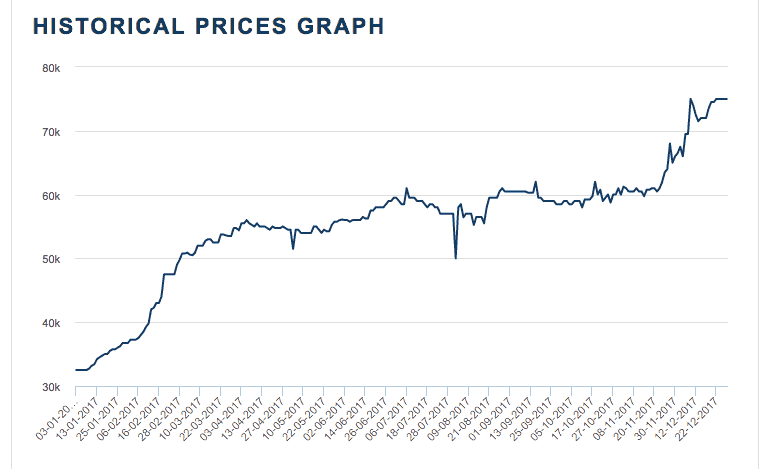

First, it’s important to realize the dramatic increase in the price of cobalt caused by new demand outstripping available supply: cobalt prices have more than doubled in the past year alone. That fact is the basic economic background for all other industry-specific cobalt supply chain challenges. In an October 2017 study published in Joule called “Lithium-Ion Battery Supply Chain Considerations: Analysis of Potential Bottlenecks in Critical Metals”, authors Elsa Olivetti, Gerbrand Ceder, Gabrielle Gaustad, and Xinkai Fu identified some major risks to the global cobalt supply, especially as demand is expected to increase from 50 kt of cobalt in 2016 to between 136 and 330 kt in 2025. Global production is largely concentrated in the war-torn, unstable DRC, and global refinement is largely concentrated in the United States’ biggest rival, China. The $1.2B trade flow represented by the Congo’s export of cobalt to China comprises 40% of the world’s cobalt trade.

“Our analysis finds that while Co[balt] supply will meet demand for the lower estimates of demand for LIBs [lithium ion batteries], there is a potential for availability concern if there is rapid vehicle adoption,” the study’s authors wrote. What counts as ‘rapid vehicle adoption’? The study’s authors specifically cited Tesla’s “aggressive targets for its lower-cost Model 3”, the car that Tesla is supposed be making at a rate of 500,000 per year by the end of 2018. When asked if he worries about lithium supply during the 3Q17 earnings call, Tesla CTO JB Straubel said that he worries more about cobalt, which is used in the cathode of Tesla’s battery cells. Indeed, Tesla is facing a cobalt cliff, a looming supply crunch that will keep Tesla from ever producing the number of Model 3s it told its investors it would produce in 2018.

Tesla’s cobalt cliff involves more than the overall global supply of cobalt—it has to do with who supplies Tesla with its cobalt and what their capacities are. Tesla’s chief partner in battery production is Panasonic, which gets its cathode powder from Sumitomo Metal Mining. Elon Musk promised stakeholders a Model 3 run rate of 500,000 cars by the end of 2018, but Panasonic cannot support more than half of that number. And Panasonic can’t get more cathode powder because its supplier, Sumitomo, is already using 100% of its cobalt production to meet Panasonic’s demand. Furthermore, cobalt refined in China is unavailable to non-Chinese customers, and most of the remaining refined cobalt is used for industrial purposes or small consumer electronics. Electric vehicle manufacturers get the scraps.

John Petersen, who’s developed an expertise in metal supply chains in his articles for Seeking Alpha over the past few years, put Tesla’s problem quite succinctly: “When one separates cobalt refined in China from cobalt refined elsewhere and further separates non-Chinese cobalt based on end use, it becomes clear there’s almost no cobalt for non-Chinese automakers.”

So that’s the first big problem for consumers of cobalt: tight supply, skyrocketing prices, and a global supply chain vulnerable to geopolitical risks of various kinds. The second big problem for consumers of cobalt is the abominable labor practices found in cobalt mines across the world, but particularly in the DRC. The country has been embroiled in a series of civil wars since Rwanda’s Hutu-Tutsi conflict spilled over the border in 1996. Up to 5M people have been killed in the long conflict, which has exacerbated disease outbreaks and famines. 400,000 women are raped every year in the DRC.

The bloody, anarchic state of nature prevailing in the country has enabled warlords to seize control of the DRC’s copper-cobalt deposits and force children to harvest ore. In November, Amnesty International issued a report calling out industry giants for failing to perform even ‘minimal’ due diligence regarding the sourcing of their cobalt supplies. “Our initial investigations found that cobalt mined by children and adults in horrendous conditions in the DRC is entering the supply chains of some of the world’s biggest brands. When we approached these companies we were alarmed to find out that many were failing to ask basic questions about where their cobalt comes from,” said Seema Joshi, Head of Business and Human Rights at Amnesty International.

Credit should be given to Apple, who has done the most to increase transparency into its cobalt supply chain. Apple was the first major company to publish the names of its cobalt suppliers, and wrote “There’s absolutely no excuse for anyone under legal working age to be in our supply chain,” in its most recent Supplier Responsibility Progress Report. Other companies are doing far less. “Microsoft, for example, is among 26 companies that have failed to disclose details of their suppliers, like the companies who smelt and refine the cobalt they use. This means Microsoft is not in compliance with even the basic international standards,” wrote Amnesty International.

Among electric vehicle manufacturers, Amnesty found that while Tesla and BMW had taken ‘moderate’ action, General Motors, Volkswagen, Fiat, Chrysler, and Daimler had only taken ‘minimal’ action and Renault had taken no action.

A February 2017 investigative report by Sky News shed light on the abusive labor practices in Congolese cobalt mines (see video below):

Images of an 8 year old boy named Dorsen being physically threatened by his supervisor in a muddy, open air cobalt mine went viral. Large brands responsive to consumer perception will be forced to further scrutinize their cobalt supply chains and bring them into compliance with international law—this will likely tighten supply even further, and increase the cost of mining and smelting cobalt. If that doesn’t happen, the alternative is worse: increasing human misery to meet demand for futuristic cars promising to save the environment.

Stay up-to-date with the latest commentary and insights on FreightTech and the impact to the markets by subscribing.