An increasingly common mantra among ship owners is that newbuilding orders are slowing in response to the growing pace of regulatory and technological change. Is this true, or just wishful thinking?

According to this theory, it is more difficult to order now – and get financing for orders – because the regulations and the technology to comply with them will dramatically change within the lifespan of the vessel (commercial ships are generally depreciated for accounting purposes over 25 years).

The shifting landscape would theoretically require new propulsion types, new fuels and new designs. A ship built today would therefore be at a competitive disadvantage to future newbuildings. The risk of premature obsolescence equates to a residual value risk, i.e., the future resale value may be too low, undercutting the rationale for ordering.

The newbuilding dilemma

The issue was raised on a Capital Link webinar held on July 2 that focused on the liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) sector. This category of vessels faces a particular challenge with newbuildings, related to fuel use.

The IMO 2020 rule will require the use of fuel with a sulfur content of 0.5 percent or less starting next year. Many believe that the best option for LPG ships will be to switch to using LPG (propane) as fuel, which will require a vessel design that is not currently on the water.

Peder Carl Gram Simonsen, chief financial officer and interim chief executive officer (CEO) of Avance Gas, commented, “When it comes to newbuildings, the future of this market, as we’ve already seen in the LNG [liquefied natural gas] shipping sector, is a dual-fuel engine using LPG as fuel for propulsion. We’ll see new technologies and new designs developed. The next generation of VLGCs [very large gas carriers] will probably use LPG for propulsion.”

John Lycouris, CEO of Dorian LPG (USA) LLC, a subsidiary of Dorian LPG (NYSE: LPG), agreed. “LPG will be much easier to use than LNG. It’s easier to store and easier to find. It will also be cheaper than the very low sulfur fuel [compliant with IMO 2020].”

Charles Maltby, CEO of Epic Gas, opined that IMO 2020 is just the warm-up for shipping’s target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent by 2050, which is likely to compel more significant design changes.

“We as ship owners are all used to making long-term decisions. We think in terms of 20 to 30 years. In a way, IMO 2020 is just a little blip – a little tiny step for us – compared to where we’re headed in 2050,” he said.

Mats Bye, an analyst at DNB Markets who served as moderator of the Capital Link webinar, noted a potential consequence of the newbuilding dilemma.

“Is there a chance that, because today’s technology could be very old technology in just a matter of five to 10 years, it could be a strong limiting factor on orders being placed?” he asked. Bye speculated that if so, shipyards could become desperate enough to seek to win orders for ships using old technology by lowering the price.

The newbuilding obsolescence issue was also raised repeatedly at the Marine Money Week conference held in New York on June 17-19.

Mats Berglund, CEO of Pacific Basin Shipping, argued at that event, “To order a newbuilding today would be absolutely crazy. Given the new technology we have coming, we do not think you could get 20 to 25 years out of a newbuilding with an engine built to burn heavy fuel oil. The new ships will have completely different engines and technology.”

A different perspective

These arguments certainly seem compelling. There does appear to be new technology coming, and new regulations. The newbuilding ordering activity has indeed slowed down this year.

But the argument that newbuilding orders should be held back due to concerns over lifespan limitations is a convenient argument that benefits existing ship owners. Over its history, the shipping industry has been notoriously unable to control its contracting activity, which has led to perennial overcapacity and rate headwinds. All else being equal, technology- and regulatory-related barriers to newbuildings would limit capacity growth, which would raise revenues for ship owners and raise costs for cargo shippers.

FreightWaves asked VesselsValue, a U.K.-based shipping data and analytics company, for its statistics on ordering activity and for its opinion on what is causing the order slowdown. VesselsValue senior analyst Court Smith offered a different perspective than the ship owners.

He said, “I’m sure there’s some trepidation around obsolescence in some market segments, but modern ships only have a lifespan of 20 years. The regulatory regime around shipping is tightening, but new vessels built to the latest standards will almost certainly be able to compete in the trades they are designed for through their expected service life.

“I think we are seeing a more normal trend in shipping, which is low rates in many markets, lack of investor interest, rising newbuild order costs and temporary oversupply in some markets,” said Smith. “Orders are drying up as a result, which in turn will lead to higher rates and tighter supply as ships come off the water. Basically, orders are slowing due to the normal shipping cycle.”

How 2019 orders are stacking up

The VesselsValue data does show a slowdown in orders, but not an unprecedented one. Despite all of the fears about pending regulations and rapidly evolving technology, owners continue to place contracts for newbuildings in 2019.

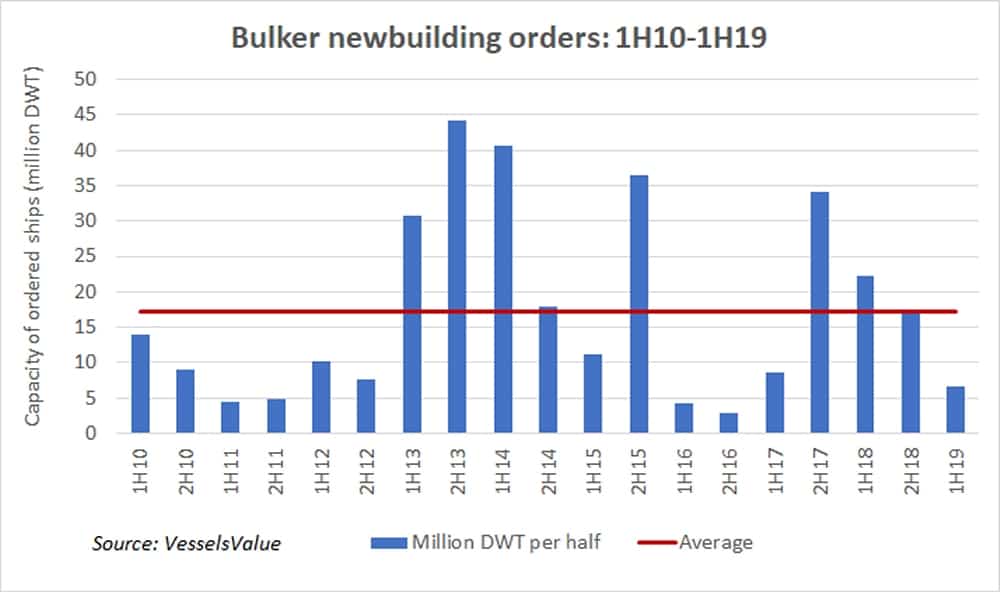

In the dry bulk sector, VesselsValue data shows that bulkers with total capacity of 6.6 million deadweight tons (DWT) have been ordered in the first half of 2019. That is 62 percent below the average for six-month periods starting in January 2010 and only one-sixth of ordering volume in the most recent peak period of the second half of 2013. However, ordering activity was even lower in 2016 and in 2011 than it has been this year.

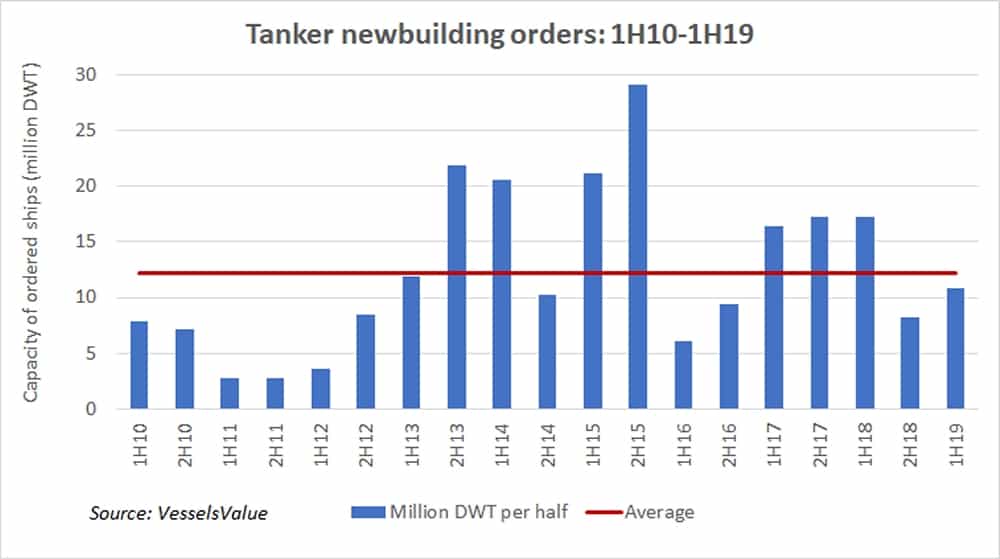

In the tanker sector, ships with 10.8 million DWT of capacity were ordered in the first half of this year. This is only 12 percent below the average since 2010. It is also a higher six-month tally than seen in the second half of last year, as well as in 2010-12 and in 2016.

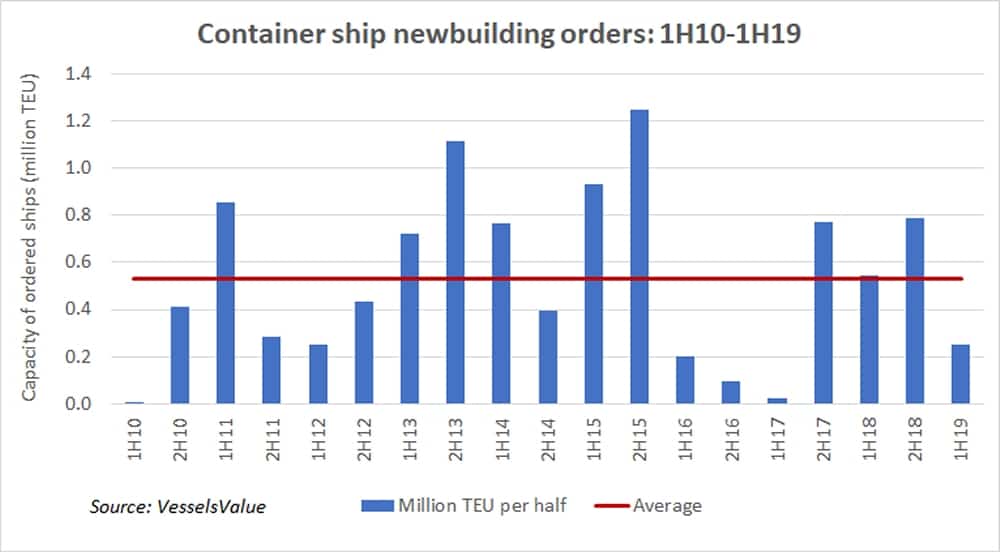

Container ship orders are down significantly. During the first six months of this year, ships with a total capacity of just 252,322 twenty-foot-equivalent units have been ordered. The pace is 52 percent lower than the average. That said, the ordering pace was even slower in 2016 and the first half of 2017.

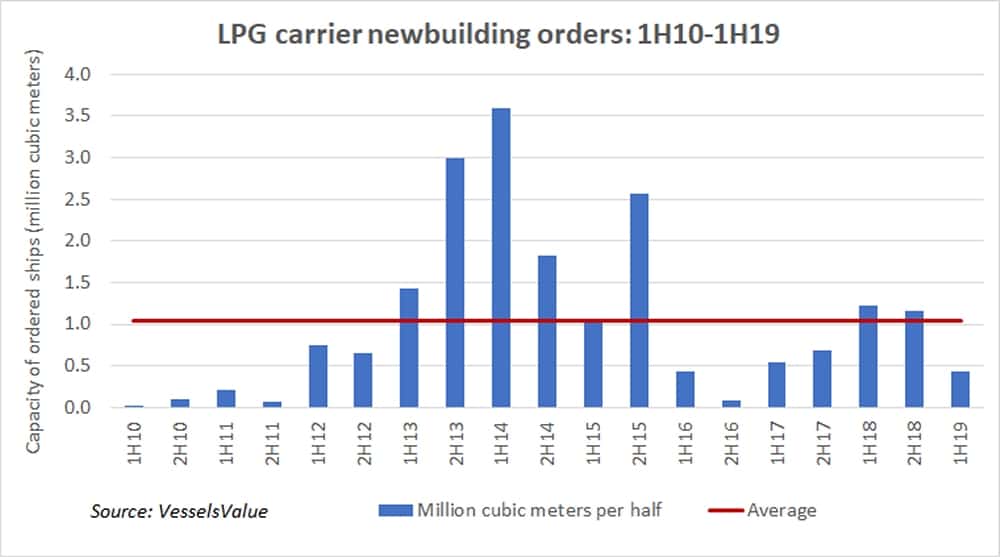

In the LPG sector discussed during the Capital Link webinar, VesselsValue data shows that ships with a total carrying capacity of just 435,200 cubic meters have been ordered in the first half of this year, down 58 percent from average. However, the ordering pace was even lower in 2010-11 and in 2016.

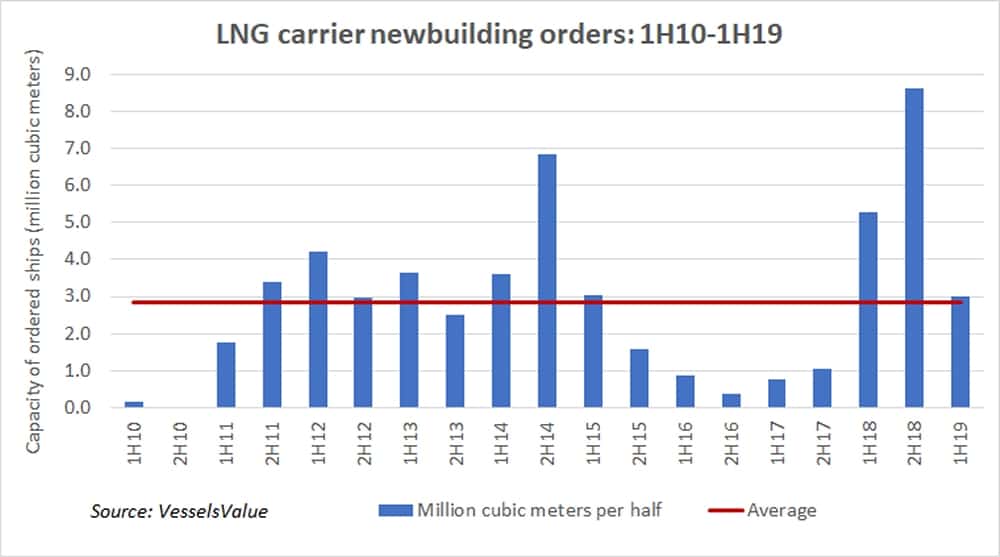

Finally, in the LNG shipping sector, the obsolescence fear is less likely to be a constraint on ordering. As explained by GasLog Ltd (NYSE: GLOG) CEO Peter Livanos during Marine Money Week, LNG carriers have already undergone rapid technological advancement. Furthermore, they already have engines allowing them to use LNG as fuel, which will provide them a cheap compliance method for IMO 2020.

Consequently, LNG ordering should be more likely to be based on purely market factors, and indeed, with LNG charter rates high, ordering activity has been elevated. Newbuilding contracts surged to record levels in 2018, and while they are down in 2019, they remain high. LNG carriers with total capacity of 3 million cubic meters have been ordered in the first half of 2019, which is actually 6 percent above the average for six-month periods since 2010.

Jason Silber

Excellent read.