Though the industry debates over driver safety, hours of service, shipper detention times, high driver turnover, and driver shortages, it still misses an important component that drives human performance.

FreightWaves Market Expert Dean Croke recently took a look at the subject of sleep in a two-part series published in Weekend Edition, a newsletter sent exclusively to FreightWaves’ SONAR subscribers. That series will be republished on Truckload Indexes.

This week we’ll take a deep dive into the science of sleep and explain why it’s the missing component in the current Hours of Service debate about “flexibility” – the one word that will change everything.

Hours of Sleep: The missing link

The biggest issue with the entire hours of service debate is that most people are focused on the wrong thing, completely missing the point of the process, which is to keep tired drivers off the road. If that’s really the goal of the hours of service regulations, then regulating sleep has to be a core component of the current “flexibility” debate.

Why it matters: A commercial truck driver can be 100 percent compliant with hours of service regulations, yet sound asleep at the wheel at the same time. This means safety and compliance aren’t mutually exclusive, with one study showing drivers on paper logs recorded a 30 percent lower U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) Recordable Accident rate compared to drivers using electronic logs. The difference is because paper logs afforded drivers a degree of flexibility that allowed them to schedule work and rest periods around their preferred sleep preference and sleep personality (but record something different in the log). Many safety experts say that this non-compliance is unsafe when in reality it’s the opposite from a driver’s perspective (because they actually sleep when they are tired).

The reverse is true today with ELDs. Time is recorded digitally, forcing drivers to often drive when tired and then attempt to sleep at times of the day when it’s impossible to do so (such as during daylight hours).

Exacerbating the problem are prescriptive rules including the “14-hour clock,” which prohibits driving beyond the 14th hour of work regardless of sleep and rest breaks within that time frame. Since research shows a 30-minute nap can give a driver a four-hour boost in alertness, not allowing naps to extend the workday would seem illogical at best.

The physiology of sleep tells us that humans are hardwired nocturnal sleepers and have evolved to wake at sunrise and begin the sleep process when the sun goes down. Even though there are hundreds of circadian rhythms (24-hour cycles) that drive the sleep-wake process, light (and in particular blue light), is the single most influential factor in determining when we sleep and wake. To understand the power of light, think about those times when you have traveled to another country and experienced “jetlag” where you “jet” to a new time zone but your body clock “lags” behind you. It takes quite a few days to adjust your body clock to the new time zone. For most people, it takes one sunrise in your new destination to move one time zone closer, so if you fly to London from New York it will take five sunrises in London for your body clock to move through five time zones.

Why the sky is blue is fundamental to understanding the sleep-wake process and why truckers are so out of sync with hours of service regulations and so passionate about flexibility. The sky is blue because that’s the color that gets refracted the most. This is because of blue’s shorter wavelength bouncing off molecules in the air and scattering its light more than other colors. At sunset we see more red and orange colors in the sky because the blue light has been scattered out and away from the line of sight. As a result, our eyes are sensitive to blue light which is also why you have a “Night Shift” setting in your iPhone display settings to reduce blue light at night.

To demonstrate how the timing of light impacts truck drivers, let’s look at common situation in which drivers who works at night drive through sunrise and in the process receive the blue light signal via the optic nerve. This signal tells the body clock to begin the waking process in readiness for another day of peak activity. In this example. the drivers’ 10-hour break now starts at 9:00 a.m., which means that even though they feel extremely tired, they are unable to sleep because their brains are trying to wake them up. This is why drivers who sleep during the day only manage (on average), four and one-half hours of sleep per 10-hour block. Compounding the problem is their sleep quality is severely diminished as “day sleep” is more fragmented and lighter in nature.

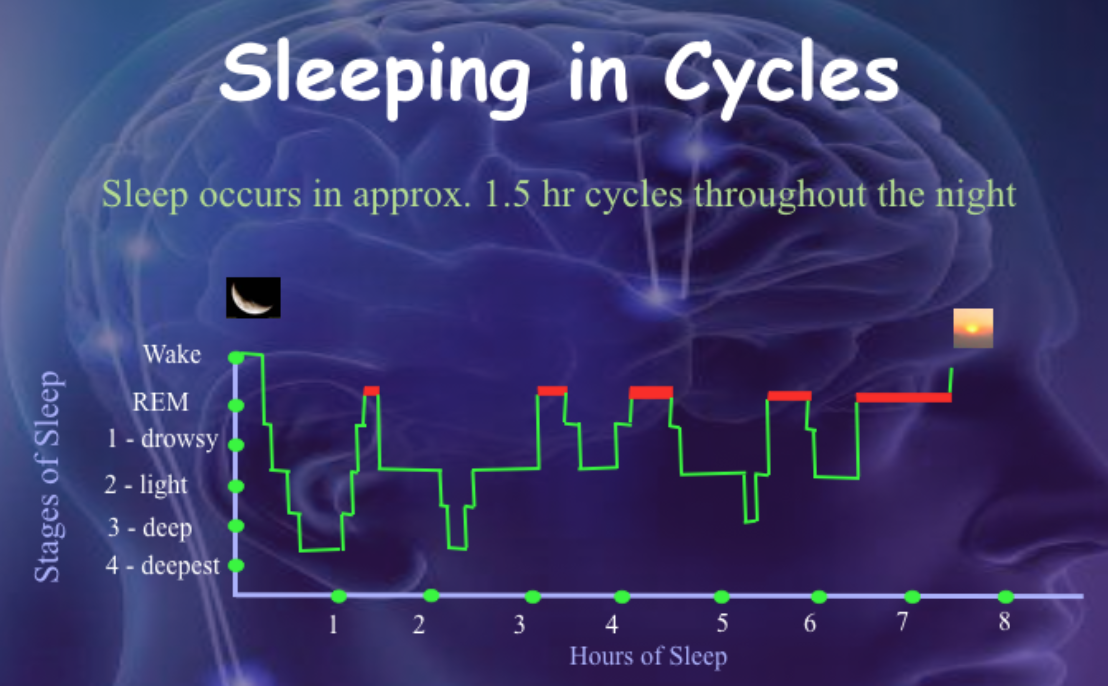

Measuring sleep in “cycles” and not hours: One of the myths about sleep is that the more of it you get, the better you feel when quite the opposite can be the case. Six hours of sleep is better than seven, yet seven and one-half is better than six – why is this case?

Human sleep follows what’s known as an ultradian cycle, in which events occur every 90 minutes – sleep cycles included. When you drift off to sleep your brain goes through various stages in succession over an approximate 90-minute period – light sleep, deep sleep and REM (rapid eye movement). Deep sleep accounts for about 75 percent of night sleep with REM accounting for the remainder, but what sets them apart is the restorative functions they perform. During deep sleep your brain is unconscious but your body is tossing and turning – you can’t hear things such as a baby crying or a heavy thunderstorm. Your body is effectively in the repair shop where the Human Growth Hormone (HGH) is released, facilitating the maintenance and repair of bones, ligaments, muscles, skin, organs and hair. Think of deep sleep as the time when physical fatigue is dealt with.

REM sleep is quite the opposite and occurs towards the end of the 90-minute sleep cycle as the brain begins to wake and major muscle groups go into a state of paralysis so that you don’t act out your dreams. Your eyes stay active, which explains the REM characterization of this sleep stage as your eyes dart back and forth. During REM your brain is buzzing with electricity – so much so you could power a 10-watt light bulb from this stage of sleep. This phase of sleep is the mental restorative process and deals with learning, mood, emotion and memory consolidation.

You dream in all stages of sleep, it’s just that during REM your dreams are the most vivid (and at times bizarre). Over the course of a night, dreams increase in frequency and intensity with the last sleep cycle being mostly REM – that’s why your most memorable dreams are the ones that occur just before you wake.

Good quality sleep comes from getting all stages of sleep over the 90-minute period and if you’ve ever woken from a one-hour nap (the most common duration of naps for truckers) and felt worse, now you know why. When you wake at the one-hour mark you experience what’s known as sleep inertia – you feel groggy, tired, lethargic, and moody. Sleep inertia lasts about 20 minutes before it dissipates. This means your new napping strategy should include either short 20- to 30-minute “power naps” (ending just before the brain drifts into deep sleep) or blocks of 90 minutes to coincide with the end of a REM period (when the brain is already wide awake).

The key to a great night’s sleep is simply putting together multiple blocks of 90 minutes, meaning sleep duration should now be measured in sleep cycles of multiples of 90 minutes. (1.5, three, 4.5, six hours and so on). The bare minimum the human brain needs is six hours of sleep every 24 hours, which is why most performance-based hours of service programs mandate six hours of continuous sleep during the off-duty period with naps being supplemented at various times adding to the daily cumulative total.

Here’s what a great night’s sleep would look like if your brain was wired up with scalp electrodes that measure the change in voltage between neurons during the different sleep stages:

(SOURCE: Sleep Science Consulting)

Setting you alarm clock: Armed with this new knowledge of measuring sleep in 90-minute cycles instead of just hours, the next step is to learn how to set your alarm clock and ensure you wake at the right stage of a sleep cycle. Most of us do it backwards – we set the alarm clock based on what time we have to be at work and are either waking before the alarm (at the end of a REM cycle) or not hearing the alarm at all because we’re in deep sleep mid-cycle.

The next time you set your alarm clock, set it to coincide with the end of a full sleep cycle. If it takes you 20 minutes to fall asleep, and you have an 8-hour block of time before you have to get ready and go to work, set your alarm clock for five sleep cycles or 7.5 hours plus 20 minutes. However, if you only have seven hours of sleep opportunity time, set the alarm to coincide with four sleep cycles or six hours plus 20 minutes. You should avoid setting the alarm clock if you’ll be forced to wake during the middle of a sleep cycle. It may sound counter-intuitive to wake before your alarm and get out of bed, but you will feel much better because you will have avoided sleep inertia (which at times can last all day).

Tips for a Great Night’s Sleep: Setting the stage for sleep is as important to understand as the physiology of sleep itself. The onset of sleep coincides with the “sleep gate” opening, but before it does, there are things you have to get right:

-

Temperature – you sleep best when your body temperature is coldest. Make sure the room temperature is cooler than normal, and around 65-66 degrees Fahrenheit seems to be a favorite for most expert sleepers

-

Light – your sleep environment has to be as dark as possible, and by “dark” we mean so dark you can’t see your hand in front of your face. Even go as far as turning your alarm clock away from you so that the green or blue LED lights don’t trick you brain into thinking it’s daylight outside. If you’re a shift worker then heavy double insulated drapes are a must

-

Noise – depending on whether you are a light or deep sleeper, noise can be both soothing or disruptive. If you’re a light sleeper then “white noise” is a great idea as it will act as a blocker to loud and infrequent noises from outside that occur during REM (if you’re going to wake during the night it will be approximately every 90 minutes). White noise in the form of a fan or similar device will help keep you stay asleep.

Avoiding sleep stealers is also something to work on, with the most disruptive being soda and coffee. Both contain caffeine, which acts to suppress feelings of tiredness over the course of a day. The main points to remember about caffeine are:

-

It takes about 20 minutes to reach the brain-alerting receptors before taking effect (so drink coffee before a 20-minute nap so you wake right on cue)

-

It has a half-life of about six hours, which means that if you have a coffee that contains 200 milligrams of caffeine around 4:00 p.m., at 10:00 p.m. 100 milligrams will still be trying to keep you awake (possibly delaying the opening of the sleep gate).

The general rule with caffeine is avoid it after 3:00 p.m. or 3:00 a.m. depending on which shift you work. That way the alerting effects of caffeine will have worn off sufficiently allow you to drift off to sleep.

In the next edition we’ll take a deeper dive into the design of biocompatible schedules and how to build flexibility into daily operations by incorporating the science of sleep.