This is part of our ongoing weekly feature called the “Online Haul of Fame.” FreightWaves will feature companies that have had a lasting impact on the trucking industry, past or present. Check out the Online Haul of Fame series posted each Friday on FreightWaves.

If you had to name one of the most influential companies in trucking history, Consolidated Freightways (CF) would be near the top. While the trucking company, CF is no longer with us, the legacy of CF lives on through the companies it spun off, including Freightliner, CNF (which became part of XPO) and Purolator International.

CF Freight, affectionately referred to by truckers as “Corn Flakes,” was founded in 1929 under the name Consolidated Freightways by Leland James. The company got its start in Portland, Oregon. The company was founded when James combined four short-haul companies located in Portland into one trucking firm. Once these companies were combined, James focused on expanding their reach.

At the time, trucking in the West was a fledgling industry. The lack of industrial expansion to the West at this point made any sort of progress difficult to achieve. Because of this, James focused primarily on establishing CF Freight as a force in Portland and the surrounding areas. Only after he achieved considerable success did he consider broadening the company’s horizons.

Almost immediately after the company was founded, the Great Depression devastated the citizens and industries of the United States. Competition was fierce, and rates were low as a result. While many companies went under, unable to stay afloat in such desperate conditions, companies like CF were large enough to wait out the lean times.

Occasionally, CF even benefited by picking up customers that had been dropped by other carriers that could not withstand the Depression. CF’s biggest competitor at the time was the railroad, which was reliable, but often slow and unpredictable. In 1935, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which had for decades regulated the railroads, began to regulate the growing trucking industry as well.

Following regulation, Consolidated proved itself a force to be reckoned with. Its routes encompassed Washington, Oregon and California, no small feat considering the initial challenges presented by the lack of infrastructure in the West. More opportunity for growth arrived during World War II. The railroads that had previously been responsible for much of the interstate transportation of freight now were moving war supplies. Trucking companies were able to step up and fill the gaps left behind by the railroads, and CF seized the opportunity.

By the war’s end, Consolidated Freightways had added dozens of new terminals throughout the western United States and had extended its service as far east as Chicago. By 1950, revenues stood at $24 million, and the company was operating 1,600 pieces of freight equipment. Because the ICC regulated rates and routes, the best way for companies to grow was through acquisition. Consolidated Freightways began an aggressive acquisition strategy, and by the end of the 1950s it had acquired an incredible 53 of its former competitors.

The 1950s also saw CF’s expansion into manufacturing. Immediately following World War II, James founded Freightliner Corporation in order to supply Consolidated with lighter, larger and more sophisticated trucks and trailers to ensure that the company remained on the cutting edge of the competitive industry. Initially, Freightliner would only build for Consolidated, but in 1951, it signed an agreement with White Motor Corporation, which was based in Ohio, allowing its trucks to be sold through dealerships. The partnership continued for 25 years. After business was established at Freightliner, James’ successor, Jack Snead, added other manufacturing interests to the family of companies. Transicold Corporation manufactured railway components, and Technic-Glas Corporation manufactured glass fiber products.

These manufacturing endeavors, coupled with the expanded truck lines, doubled Consolidated’s sales while Snead was at the helm. In 1959 Consolidated hit $146 million in revenue, making it the largest common carrier in the United States. At the time, Consolidated had grown to employ nearly 11,000 people, while operating 13,800 pieces of equipment in 34 states as well as Canada. This success was misleading, however, as the company learned in the 1960s.

While the family of companies had grown, leadership had failed to integrate them effectively. This, combined with an economy in recession, lead to a $2.7 million loss at the end of 1960. Snead was asked to step down, and William G. White was named chairman and president of Consolidated Freight. He found that, for all of Consolidated’s acquisitions, integration was sorely wanting.

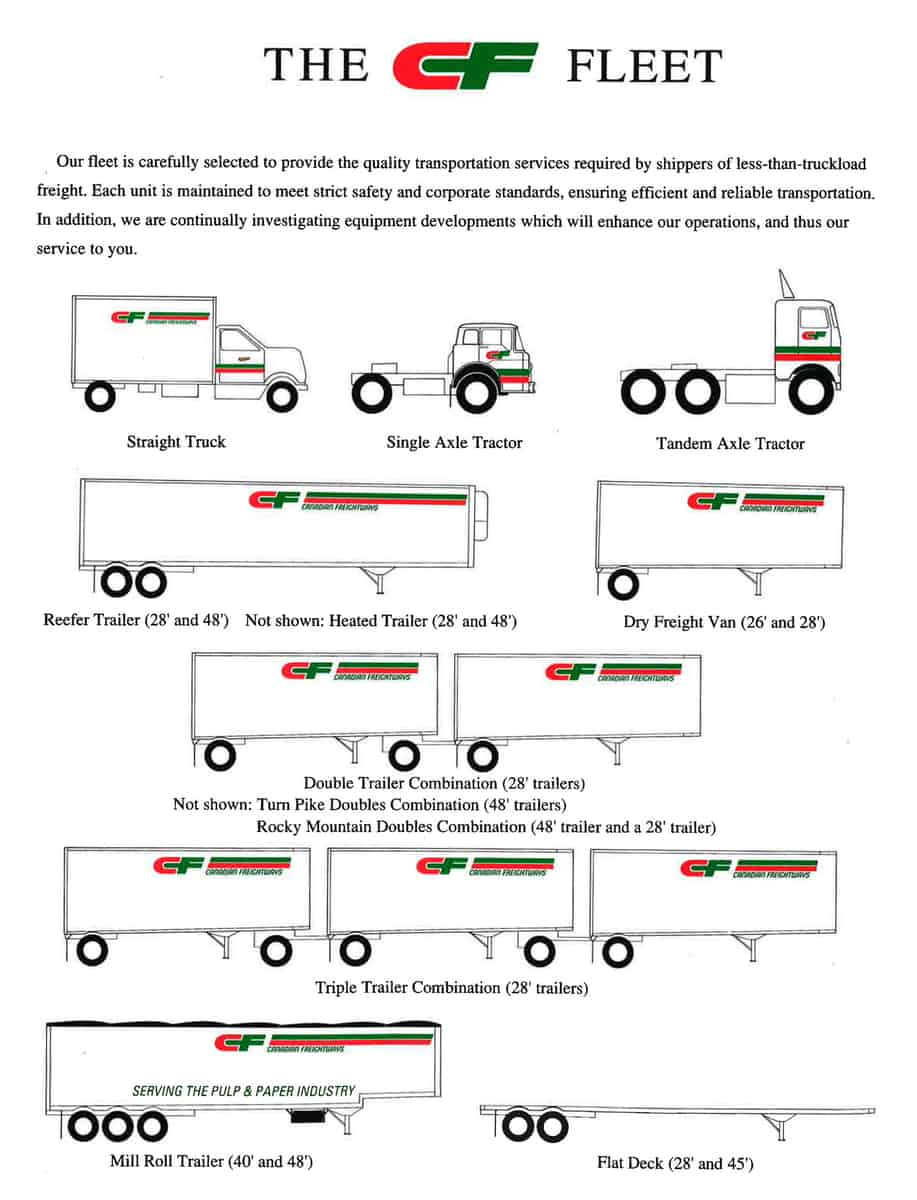

White immediately set out to integrate the companies, focusing on coordinated control from headquarters, as well as service. Traffic routes were defined and terminals were consolidated. White also decided to place a concerted effort on making Consolidated a leader in less-than-truckload (LTL) freight movement, when before it had only been a participant.

White also sold off a number of the company’s subsidiaries that were more trouble than they were worth, including a small parcel company that was meant to compete directly with United Parcel Service. As a result of these actions, Consolidated’s revenues increased at an average of 15% per year, and in 1969, Consolidated’s sales had reached $451 million.

The company faced more challenges in the 1970s, especially when the Middle East oil embargo threatened trucking companies as gas and diesel prices soared. Consolidated’s Freightliner endeavor was also challenged, as the industry emphasized a need for fuel-efficient equipment, as well as surviving a new government mandate regarding their braking systems that disrupted normal sales cycles.

In 1977, Freightliner severed its ties with White and began looking to build relationships with dealers and agents. Unfortunately, Freightliner could not compete with Mack and International Harvester, which manufactured more affordable equipment. CF sold Freightliner to Daimler-Benz in 1981.

In 1980, the trucking industry was deregulated for the first time since the initial regulation by the ICC in 1935. Where some saw freedom, others saw the potential for heightened competition. Rather than cling to the manufacturing endeavors under CF’s umbrella, the company elected to abandon its manufacturing interests altogether. Consolidated then created four regional trucking companies that would specialize in overnight delivery.

These four companies were doing $600 million in combined sales in the early 1990s, and CF MotorFreight, the company’s long-haul business, was also doing well. While over 50% of trucking businesses went out of business in the eight years following deregulation, Consolidated’s renewed focus and energy on its trucking endeavors allowed the company to not only survive, but thrive, just as it had done in the Great Depression.

In 1989, Consolidated’s management made a misstep that proved to be quite costly. The company had been operating CF AirFreight, its own air freight forwarding company for some time.They thought that purchasing another strong air freight forwarder could bolster the performance of CF Air Freight. They purchased Emery Air Freight Corporation, an industry leader at the time.

Unfortunately, Emery’s own subsidiary, Purolator Courier Corporation, was deeply in debt. At the time of the acquisition, the companies together were losing nearly $1 million per day, leaving Consolidated with a $41 million loss in 1990 and $614 million in debt. The CEO responsible for the acquisition, Larry Scott, was removed and replaced by Donald Moffitt.

Moffitt and Roger Curry, Emery’s CEO, set out to undo the damage that had been done. They revamped Emery’s overnight service and removed it from competition with other parcel companies. By 1995, Emery had made quite a comeback and was the air freight industry’s most profitable firm.

The 1990s were not without their challenges, however. The price wars that started with deregulation continued to decrease margins, until CF was operating on profit margins of only 1.5%. A Teamsters’ strike in 1994 lasted 24 days and drastically affected the company’s annual revenues.

Freight analysts began to question if the LTL industry could survive, calling the price wars suicidal and expressing concern about competition from smaller, non-union regional carriers. Rate discounting took a heavy toll on CF’s long-haul business, which achieved profitability only once between 1992 and 1996.

The company elected to spin-off CF Motorfreight and four other long-haul subsidiaries in 1996, renaming the group Consolidated Freightways Corporation. The remaining companies, Con-way Transportation, Emery Worldwide and Menlo Logistics, were rebranded CNF Transportation. The “new” CNF Transportation emerged from the rebranding with very little debt, and once again, could focus on its LTL offerings and expertise.

CNF and CF were operated completely differently after the split. CNF was largely a non-union operating company, while the union operations remained with the legacy CF. Following the spin-off, CNF thrived as an independent company, while CF began to struggle.

Because bankruptcies and sudden shuttering of multi-billion dollar companies don’t happen overnight, there were a number of decisions that predetermined the legendary company’s fate.

Funding Universe describes the final years of CF’s business:

“Ill-advised decisions in 1999 inaugurated a period of poor financial performance at CF. The company suffered that year from a decision to take on marginal freight, including freight from carriers that had gone out of business. In addition, the switch to a new outsourced information technology system required a large investment. As a result, net income for 1999 was $2.7 million on sales of $2.38 billion.

CF hoped to put its performance back on track in 2000. CEO Roger Curry retired in January of that year, and a new management team met in June of that year to develop a profitable strategy. The new CEO was Patrick Blake, a 30-year CF employee who had first begun loading and driving for the company in 1971. As part of its turnaround strategy, CF sold its Menlo Park headquarters in August 2000 and moved to new offices in Vancouver, Washington. The company also bought FirstAir Inc., a Minnesota-based air freight forwarder, in an acquisition designed to improve CF’s position in the expedited-transportation market. The new air division was renamed CF AirFreight, recalling the company that had operated before the 1989 acquisition of Emery. In addition, CF brought in outside experts to help it use its terminals more efficiently. Still, Blake emphasized that a turnaround would take some time. The company reported a net loss of $7.6 million for 2000.

Unfortunately, CF’s performance only worsened in 2001 as a declining economy and the impact of the September terrorist attacks in New York pushed the company’s net loss to $104.3 million for the year. The company’s administrative staff was cut from 900 to 800 in June of that year, and hundreds of other employees were laid off at sites across North America. The loss of a major account late in 2001 contributed to a net loss of $36.5 million for the first quarter of 2002.”

Try as it might, the company could not regain the ground that it had lost. Consolidated Freightways Corporation filed for bankruptcy in September 2002 and closed its doors. At the time it filed for bankruptcy, the company had 15,000 employees and was generating around $2 billion in annual revenue.

The company that had been spun-off, CNF Transportation, rebranded itself under the name Con-way, and remained in business until 2015, when it was acquired by XPO Logistics.

Other Haul of Fame coverage:

KEITH SCHULTZ

my dad was with the local 200 in Milwaukee he drove for CF for over 40 years. Working on a tractor model right now in memory of my dad. greatest event was in the summer one year he drove his city rig and stopped at the house because he “forgot” his lunch. he just wanted to show me what he did at work. thanks for the articles and the piks

Drew Beeson

Does anyone know CF drivers wore ties in the early 1970’s?

JR Ewing

This was a great read. I was linehaul in Milwaukee from 1976 till close. Was a great time in my life. So sad that it was driven into the ground. Was very hard to not be bitter. Looks like the CCX folks got the same knife.

Dan Hershberger

When I joined CCX in Dec.1983 we worked our tail off after my Lease way Co. went out of business after 27 years of Service. We had other drivers from other companies so professional drivers that lost there jobs in 1983-1987 as other companies fell as deregulation was enacted so we were were happy drivers and they treated us very well and respectful because we all wanted the company to succeed. CCX was a team success.. Never thought they would sell.

Christopher Bordeaux

Very good article, enjoyed reading it. Had relatives and friends who drove for CF in Neenah, WI