If Sea-Land founder Malcom McLean is recognized as the “father of container shipping,” then surely Charles Morgan should be deemed the “father of integrated shipping” since he was the first to offer scheduled common carrier service that coordinated his steamship company with the railroads.

Morgan was born in 1795 and grew up in Connecticut and New York. Not much is known about his early life, except that various directories listed him as a grocer and ships chandler from the years 1819 to 1833. In 1842 he was listed as a merchant and then in 1856 he was identified as a banker and steamship owner. Dun and Bradstreet credit reports from the period associated him with the Morgan Iron Works of New York, a major ship engine builder.

Morgan’s life focus was on transportation and that of being a common carrier. He got a start in ship owning in 1819 by controlling a 25% share of the sailing packet ship Franklin. Of the total 35 sailing ships that he operated, each of them was owned through partnerships. These ships regularly traded between New York, Charleston, New Orleans, Havana and West Indian ports.

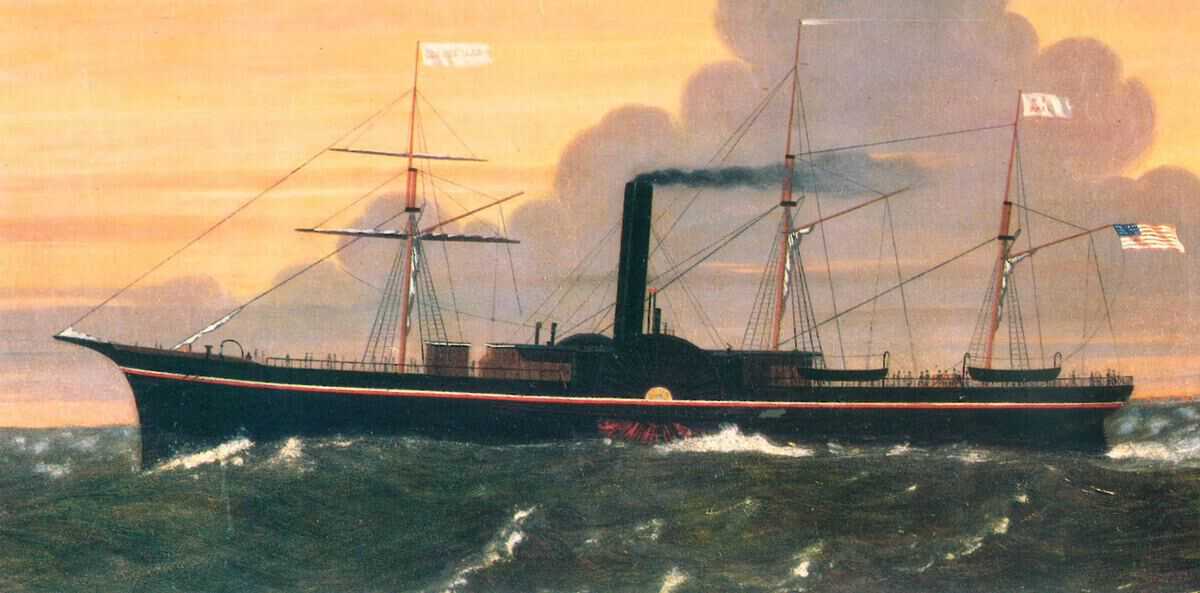

Recognizing the developments and reliability of steam-powered navigation, Morgan realized that to maintain a schedule he needed steamships and took delivery of his first side paddlewheel steamship, the 190-ton David Brown in 1833. He also bought into the T. F. Secor Co. of New York, a builder of marine steam engines. In 1850 Morgan acquired the company and renamed it the Morgan Iron Works, which was headed up by his son. Over a period of 29 years, Morgan supplied 112 engines for commercial and naval ships.

The 1800s was a boom time for American ship builders and owners. In 1817 Congress passed legislation restricting coastal shipping to U.S.-flag vessels that were American built and crewed. By 1829, the first railroad in America was built in Baltimore. America was becoming industrialized and the Northeast needed many commodities available in the South, such as cotton, leather, sugar, molasses and lumber. Cargoes and people also traveled by sea.

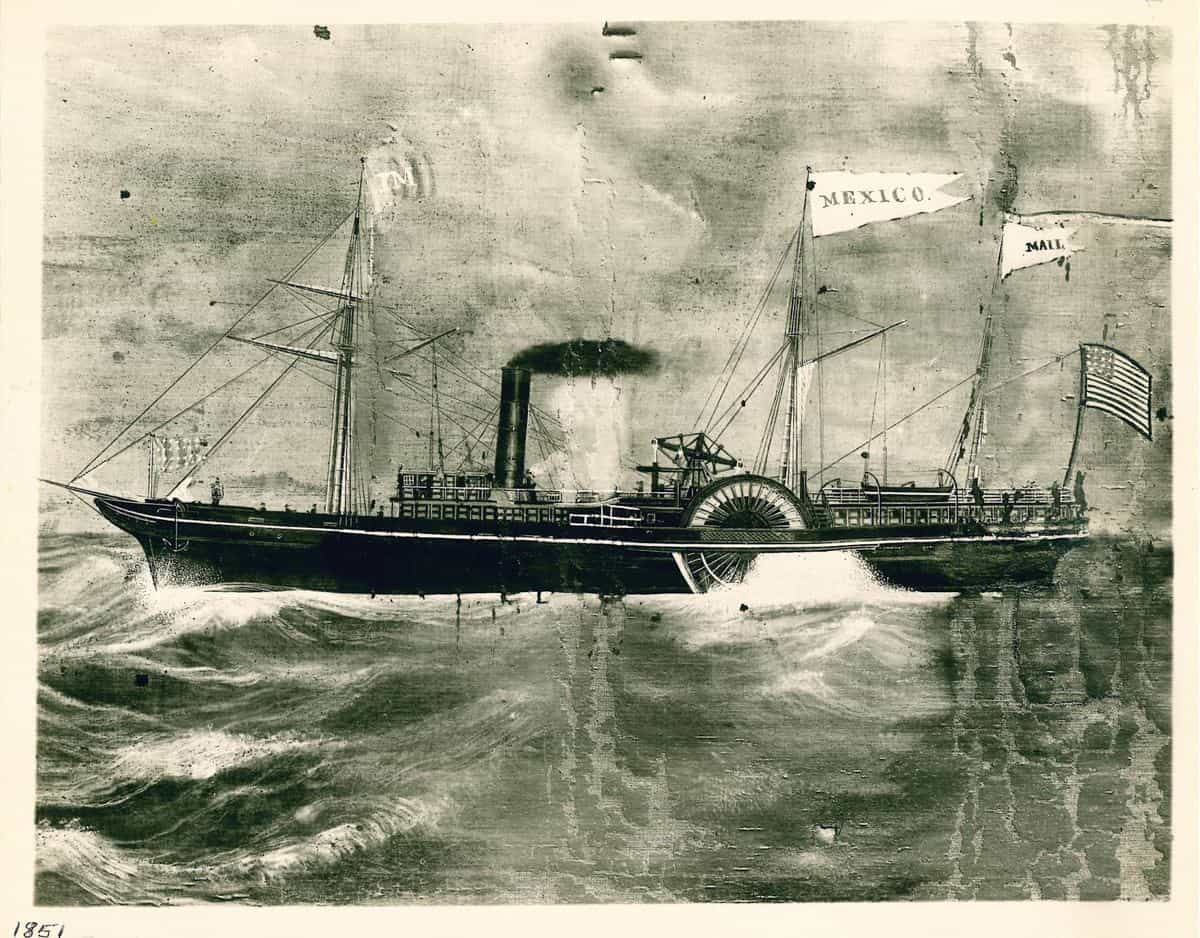

Travel through the Gulf of Mexico, however, was treacherous. In many Gulf ports, the water was shallow, pirates were numerous, navigational aids were minimal, and for sailing ships the trip up the Mississippi River against the current was time-consuming and hazardous. During the mid-1830s, the Mexican navy and the formation of the Republic of Texas added to the difficulties of commerce for the area.

On June 8, 1844, Morgan purchased his first propeller-driven ship, the SS Republic. The ship was used to open a service to the Republic of Texas, calling at Galveston, and was the first propeller-driven ship to ply the Gulf of Mexico. The Republic was Morgan’s first solely owned ship.

Texas became a state in 1845. In 1848 gold was discovered in California and thousands of miners hoping to strike it rich traveled mostly by sea to Panama or Nicaragua for the overland passage to the Pacific, where they continued their journey by ship to San Francisco. Thus, Charles Morgan became the prime carrier on the New York-to-Gulf of Mexico route.

By 1852, Morgan’s ship engine business flourished and his fleet of steamships dominated the New York, Havana, Chagres (now Cristobal), New Orleans, Galveston, Port Lavaca, Indianola, Brazos, Mexican and Nicaraguan trades. In addition to passengers, miners, and military troops, his ships handled U.S. mail and cargoes.

Assisting in control of his numerous enterprises were his son Henry and two sons-in-law, G. Quintard at the Iron Works in New York and I. Harris in New Orleans overseeing steamship operations. Charles Morgan oversaw operations in New York but traveled regularly to the ports. Three years later his third and youngest daughter married Charles Whitney, who headed the Nicaraguan operations of the company.

The expansion of Morgan’s ship fleet and services was not without problems. The treacherous western Gulf, with its sandbars, shifting currents and shallow waters, resulted in a number of his ships being lost or stranded for the company. It was about this time that Morgan realized the need for better and deeper harbor channels, proper wharves and more reliable pilotage and tugboats if his company was to successfully trade to Gulf ports. Since the government was not yet prepared for this undertaking, Morgan set up companies to accomplish all of the above.

Additionally, Morgan began investing in railroads to serve as feeders for his maritime services, which included rail-on-dock operations. Since there were few shipyards in the Gulf, he established the Louisiana Drydock Company located next to his rail and ferry operation at Algiers, La., across the river from New Orleans.

Since New Orleans by that time was the center of U.S. Gulf operations, Morgan became concerned about the high port fees, property taxes and piloting fees. Along with other investors, he formed the New Orleans, Opelousas & Great Western Railroad, which he planned to operate from his Algiers facilities west to Brashear (renamed Morgan City in 1816), on to Houston and then to the Pacific Ocean. The rail link to Brashear, with its easy access to the Gulf, was completed in 1857. It was not long before Morgan built a complex of wharves, warehouses, cattle landings and coal yards at Brashear, basing a number of his ships to the new port facilities.

On April 5, 1861, Fort Sumter was attacked, and nine days later President Lincoln ordered a blockade of all southern ports. By 1862, a dozen of Morgan’s ships were seized by the Confederacy. A larger share of Morgan’s income came from the Iron Works, which by then was the foremost American engine builder, while the remainder of his fleet served the East Coast and West Indies.

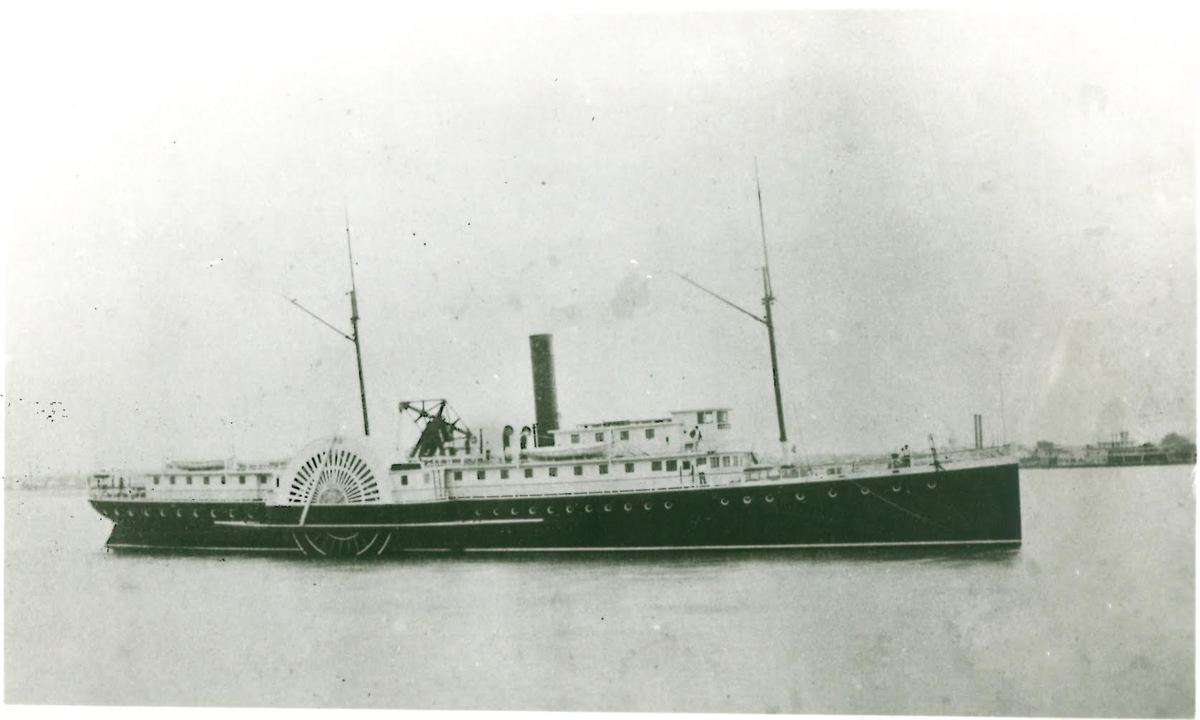

After the Civil War, Morgan’s Gulf Coast operations quickly resumed. Since there was a glut of available ships, his fleet was rebuilt. He also sold Morgan Iron Works in 1867.

For the next 10 years, Morgan established railroads to feed his expanding network of ports. His dredges also kept busy digging harbor channels to 100 feet wide and 12 feet deep at a number of Gulf ports, in addition to dredging a 120-foot-wide channel 9 feet deep to Houston.

In 1873 Morgan converted his steamships’ freight tariffs to a railroad basis to facilitate easy interchange for “through service” for his own ships and railroads from New York to Gulf and West Indies ports. His last acquisition was the purchase of the Houston and Texas Central Railroad, further extending his integrated transportation network.

In April 1878, a few weeks prior to his death at the age of 83, Morgan transferred the shares of his companies to family members. He died in New York City on May 9, 1878.

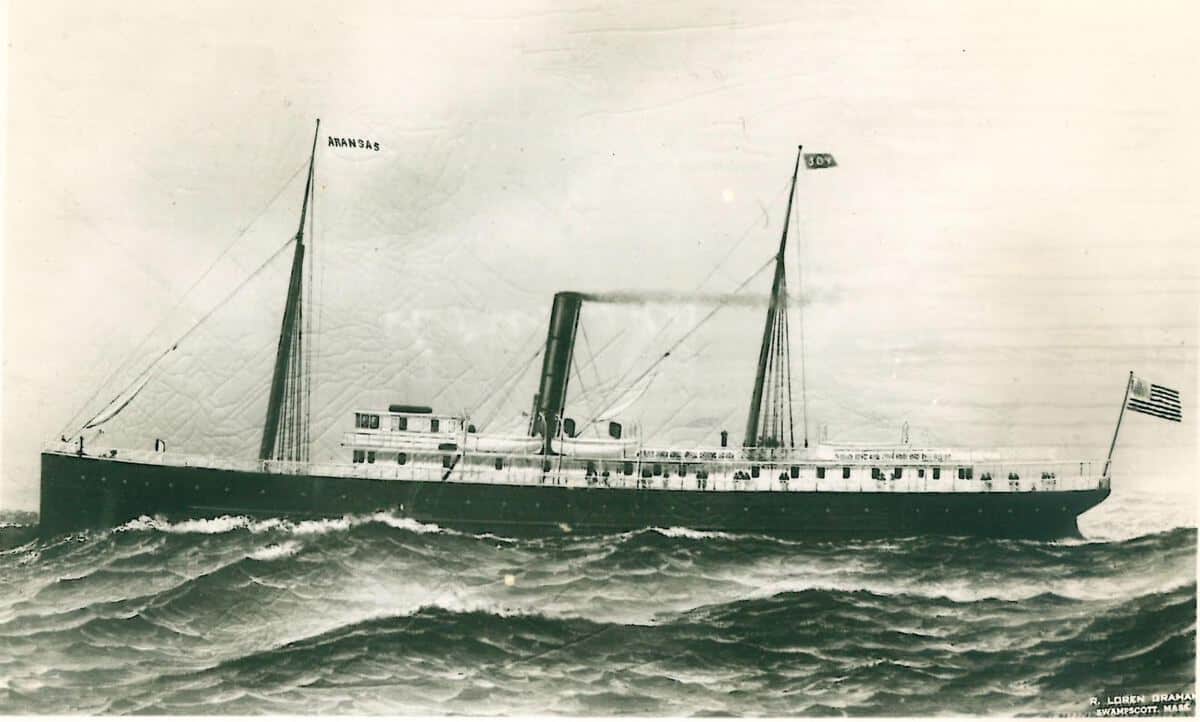

After his death, his original plans for expansion and consolidation continued under the existing management. Collis P. Huntington in 1882 bought most of Morgan’s transportation assets, incorporating them into his Southern Pacific Railroad. The ship fleets were continuously updated and their services expanded. Although owned by the Southern Pacific, the company remained known as the Morgan Line until its sale to the U.S. government at the start of World War II.

At a time when American transportation was using the stagecoach and pony express, Morgan showcased the power of steam via his steamships and railroads and had the vision to integrate both by building the necessary port infrastructure.

Elking George

You need to do some research on the first intermodal move on an Ocean and Railroad bill. Fred Babin , was with Luke’s steamship line. He approached me as the Katy Railroad’s, pricing officer, to publish a through Ocean/TOFC, intermodal rate for Banfi Wine, in Italy via the Port ofGalveston, to Kansas City, Mo., via the MKT(Katy) Railroad.

Fred, was successful in getting both the FMC and ICC’s approval. Fred and I agreed on our joint rate and the shipment happened and moved via The Port of Galveston to the Caves, in Kansas City, Mo., via the Katy RR.

George Elking

Fred