Shipping adheres to a time-honored tradition: When shipowners make exceptionally high profits, they order a lot of new vessels. When those newbuilds are delivered by the yards, it kills shipowners’ profits.

Such boom-and-bust behavior has been de rigueur for over a century. As London shipbroker J.C. Gould, Angier & Co. wrote in 1894: “The philanthropy of the shipowners is evidently inexhaustible. The amount of tonnage on order guarantees a long continuance of low freight rates.”

The container industry has experienced the most profitable two years in shipping history in 2021-22. Right on cue, owners ordered more new container ships than ever before. Even now, as freight rates tumble, they’re still ordering more.

“A huge number of new large container ships are going to hit the water at a time of stagnating demand,” warned Alphaliner in a report on Tuesday. “The market could struggle to absorb all these new ships.”

The container-ship orderbook now stands at 7.1 million twenty-foot equivalent units, according to Alphaliner shipping analyst Stefan Verberckmoes. The previous peak was 6.6 million TEUs in 2008. At that point, tonnage on order totaled 60% of the capacity of the on-the-water fleet.

Since then, the global fleet has more than doubled, so the current orderbook — a record in absolute capacity terms — represents “only” 30% of existing tonnage, noted Alphaliner.

Record newbuild deliveries in 2023-24

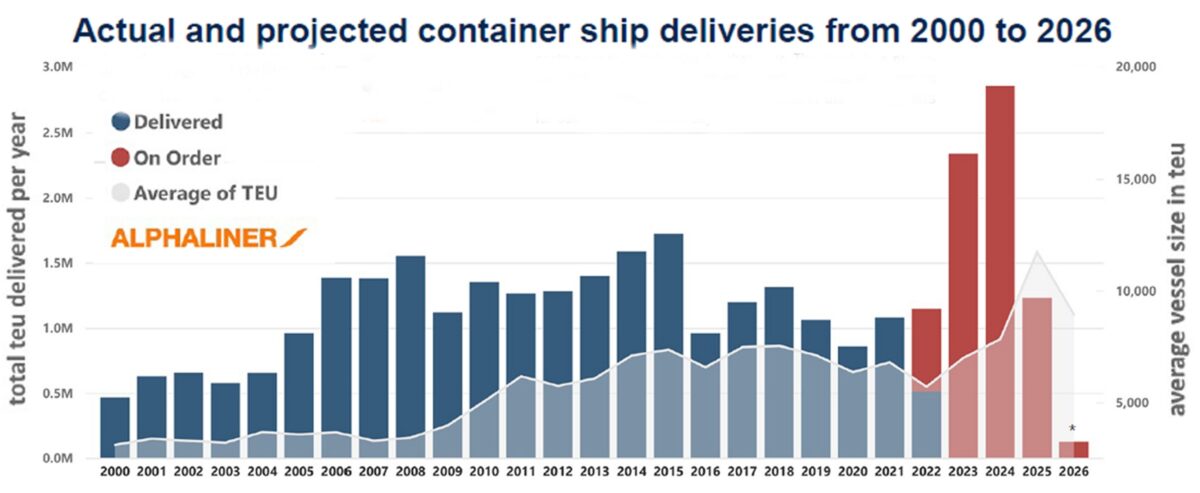

The majority of tonnage on order will be delivered the next two years: 2.34 million TEUs in 2023 and 2.83 million TEUs in 2024, compared to around 1.1 million TEUs in both 2021 and 2022, said Verberckmoes.

The scale of the upcoming deliveries is unprecedented. Historical delivery data from Clarksons shows that annual fleet growth averaged 970,000 TEUs in 2001-20. Deliveries in 2023-24 will be 2.6 times higher than that average.

The previous single-year record for annual growth was 1.7 million TEUs in 2014, according to Clarksons data, well below what’s to come.

Meanwhile, the current orderbook continues to grow. New orders favor dual-fuel tonnage that can burn both traditional marine bunker fuel as well as liquefied natural gas or methanol. Alphaliner data shows that 29% of capacity on order is dual-fuel.

Maersk announced orders Wednesday for six more 17,000-TEU newbuilds that can run on either traditional fuel or green methanol. All are for 2025 delivery. The new orders bring Maersk’s methanol-fueled orderbook to 19 17,000-TEU vessels.

Alphaliner said that MSC is reportedly near a deal for 12 16,000-TEU newbuilds that can burn LNG; Yang Ming is inviting bids for at least five 15,000-TEU vessels with LNG-fuel capability; Maersk is looking at an additional series of 2,500-TEU ships that can run on methanol; and Cosco is considering orders for six methanol-powered 23,000-TEU ships plus nine conventional 15,000-TEU ships.

Ships in existence vs. ships in service

“The jury is still out on whether the market can or cannot absorb this,” wrote Alphaliner.

Maersk CEO Soren Skou addressed this issue during his company’s Q2 2022 quarterly call. “What matters in our view in container shipping is not so much how many ships exist,” he explained. “What matters is how much capacity we deploy in our networks compared to the demand that we have.

“If you go back to 2020, demand was down sharply, by 15%, in the second quarter. But [freight] prices stayed flat because all of the networks adjusted capacity and idled tonnage that was not needed. Certainly, going forward, that will also be our philosophy. We will provide the capacity our customers need, but we will not sail all the capacity we have unless there’s demand for it.

“That’s what I see for this industry, assuming everybody continues to operate their networks the way they do today,” said Skou. “I see little reason to think people would do something different.”

“Something different” is exactly what happened in the last big downturn. Following heavy newbuild deliveries in 2014, the container industry descended into a price war in 2015-16, leading to the bankruptcy of Hanjin.

Scrapping and slow steaming

“What [carriers] do next will go a long way in determining how much of the gains of the supercycle they get to keep,” wrote Drewry in a report on Tuesday. “Failure here will mean that the industry will be doomed to return to the low-margin pre-pandemic trend.”

Carriers “face an enormous challenge taming the one thing they have control over: supply,” said Drewry. “The problem is there is a lot of it.”

If carriers idle tonnage to compensate for demand weakness in the years ahead, idled ships that are owned would still incur capital costs and idled chartered ships would still incur lease payments.

One way to offset this is for carriers to scrap older vessels. Virtually no container ships were scrapped in 2021-22 because freight rates were so high. Carriers “will look to offload as many older, more polluting ships from the market as quickly as they can,” predicted Drewry. “Our base forecast includes provision for a near-record level of demolitions in 2023.”

But Alphaliner said “it is unlikely that the quantity of ‘scrap-able’ ships will be enough to offset the supply and demand imbalance. Most certainly, younger vessels will likely need to be torched too, to alleviate the pain.”

Carriers could also throttle sailing speed, which would cut fuel costs, reduce emissions and remove effective supply. Skou estimated that environmental regulation-driven slow steaming could reduce global fleet capacity by 5%-15% in the medium term.

Expiring charters will make room for newbuilds

Another big lever for ocean carriers: They can let existing charters expire to offset newbuild deliveries.

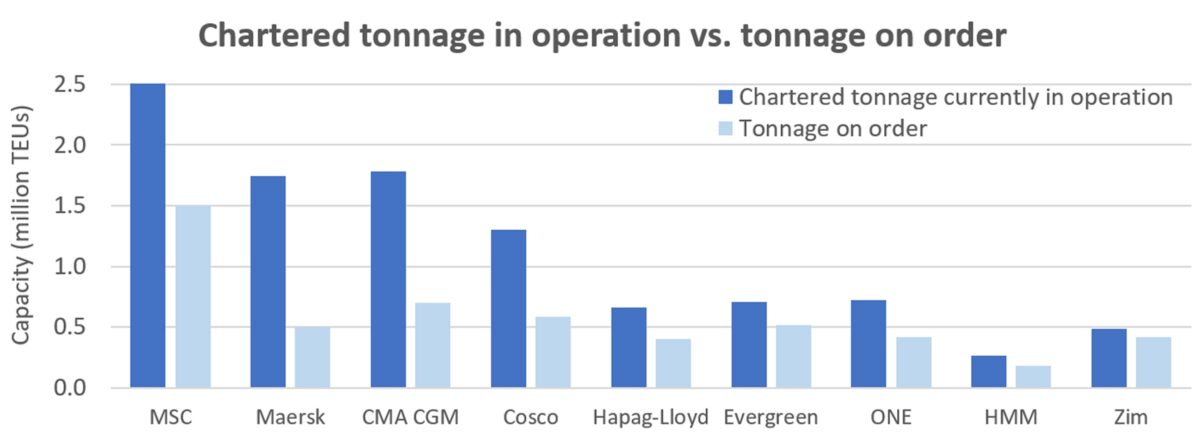

Alphaliner noted that 56% of capacity on order will either be owned or chartered by one of the top five carrier groups: MSC, Maersk, CMA CGM, Cosco and Hapag-Lloyd.

The company’s data also shows that the top 10 carriers have significantly more chartered tonnage in operation today than they have on order. This should allow carriers to make room for newly christened ships via charter expirations.

According to Alphaliner data, MSC currently has 2.5 million TEUs on charter, 68% more capacity than it has on order. CMA CGM is chartering 1.8 million TEUs of capacity, 2.5 times what it has on order. Cosco charters more than twice its orderbook. ONE has 72% more chartered tonnage in service now than it has under construction at the yards, Zim (NYSE: ZIM) 17% more.

In general, Drewry voiced optimism that the carriers could use various strategies to avoid a wipeout when the tidal wave of newbuilds hits.

Shipping lines are “entering a period of managed decline,” it said. “Following consolidation and alliance restructuring, carriers are better placed now to tackle the ‘danger’ years than ever before” and to “pull the right capacity levers to ensure a soft landing for the market.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller