Container lines provide a window into the future of U.S. landside cargo flows, not in the sense of reading tea leaves or palms, but in the sense of inevitability, like death and taxes.

Container-line schedules foretell that U.S. seaborne imports will fall sharply. That, in turn, will translate into lower trucking and rail volumes to the extent lost seaborne imports are not offset by higher volumes across land borders, by air, or from domestic producers, warehouses and distribution centers.

The latest numbers are staggering. According to Copenhagen-based Sea-Intelligence, 435 deep-sea sailings have been “blanked” (canceled) through this past Sunday as carriers retune service levels to coronavirus-reduced demand. This equates to a loss of 7 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) of container capacity to Europe and the U.S.

Further cancellations were announced after the Sea-Intelligence report was released, including sailings by the 2M Alliance (Maersk, MSC) and Hapag-Lloyd.

“Carriers are exhibiting a high degree of capacity-management discipline during the coronavirus pandemic,” asserted Sea-Intelligence CEO Alan Murphy, citing the shipping industry’s “forceful response to the market downturn.”

Forward visibility

Volumes arriving at American seaports are inherently limited by the capacity of inbound container ships. That capacity can be determined well in advance through sailing schedules. Announced departure cancellations now extend until the end of July.

It takes around 14-22 days for a container ship to transit from China to Los Angeles or Long Beach, California; it can take around 30-40 days for a transit from Asia to East Coast ports.

To foresee the pace of U.S. import reductions, take the week of departures for canceled sailings, the TEU capacities affected, and add in the transit time.

Nerijus Poskus, global head of ocean freight at Flexport, told FreightWaves that 13% of trans-Pacific sailings to the U.S. departing the week of April 6-13 have been canceled. The share of canceled sailings rose to 20% in April 13-19 and is 28% in April 20-26, 21% in April 27-May 3 and 26% in May 3-9.

Tack on two to six weeks to those dates for transits and a significant decline in U.S. imports in May and June is guaranteed.

Further downside risk

If 20% of previously scheduled arrivals at a U.S. port don’t show up, cargo imports through that gateway would decline by 20% versus what they otherwise would have been, assuming slot utilization is the same. Port volume could decline more than 20% if the noncanceled ships have decreased slot utilization.

Another downside risk is that carriers don’t cancel schedules at the same pace. “The approach to the blank sailings differs between alliances,” explained Murphy.

“The pattern is that 2M and THE Alliance [Hapag-Lloyd, Yang Ming, ONE, HMM] have chosen an approach where they announce blank sailings ranging quite far in the future — typically to the end of the second quarter — and then supplement these with additional blank sailings tactically as the situation evolves,” said Murphy.

“The Ocean Alliance [COSCO, CMA CGM, Evergreen, OOCL], on the other hand, announces blank sailings for a shorter period into the future and has not yet announced much for the later period in the second quarter,” he said. He noted that 2M and THE Alliance have blanked 19%-21% of sailings departing between May 25 and July 5, whereas the Ocean Alliance has only blanked 6% of sailings in the same period.

“Given how the pandemic is impacting the economy, it should be expected that we will see more blank sailings emerge from the Ocean Alliance in the second quarter,” warned Murphy.

Yet another reason to expect more service cancellations is that some carriers are now limiting the ability of cargo shippers to book in advance, which could disincentivize bookings. Hapag-Lloyd said on Monday that it is finding it “increasingly difficult” to manage future bookings “given the high likelihood of changes” and has decided not to accept bookings made more than six weeks in advance starting May 1.

Rates are still holding

The high degree of liner consolidation may seem like a negative for U.S. cargo shippers with international supply chains: If there were more carriers, there would be more price competition for market share, lowering transport costs.

But in the midst of a global crisis like the coronavirus outbreak, too much carrier competition could be disastrous for all stakeholders. If both volume and pricing collapse, a major carrier or carriers could go bankrupt, destabilizing the entire ocean transport system.

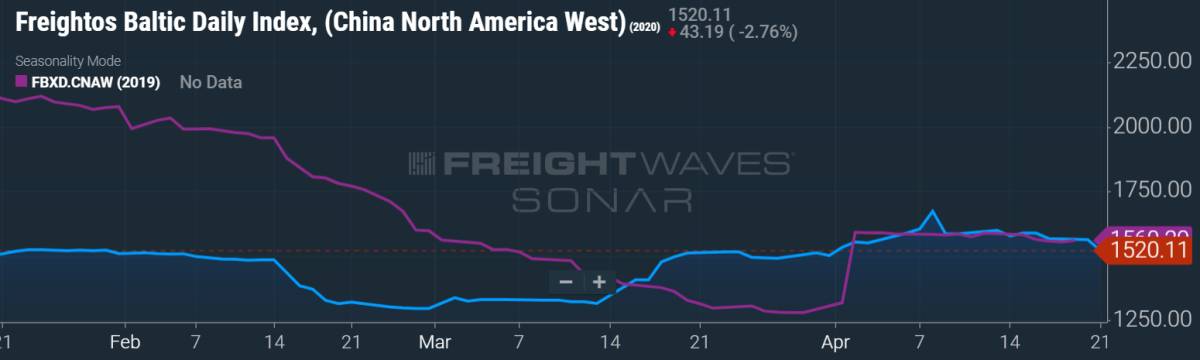

So far, carriers have kept pricing steady, which should allow them to remain solvent — assuming they can keep it up. The price to ship a forty-foot equivalent unit (FEU) container from China to the U.S. West Coast (SONAR: FBXD.CNAW) is very close to what it was a year ago, according to the Freightos Baltic Daily Index.

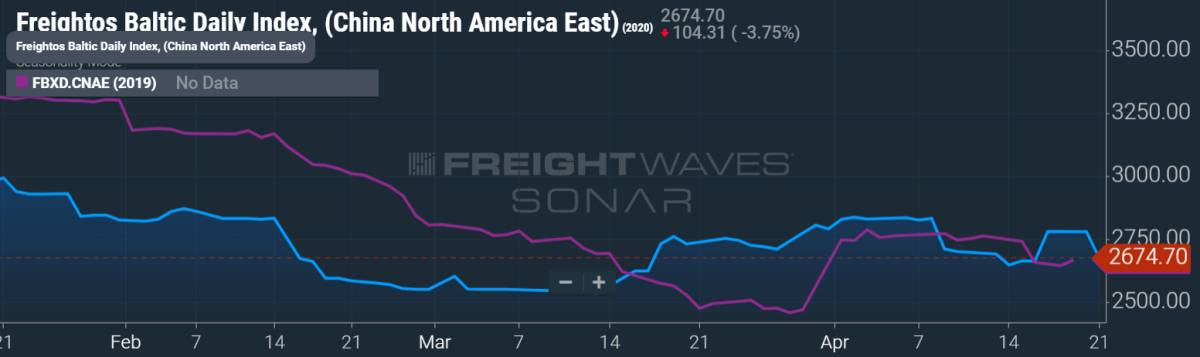

The same is true on the China-to-U.S. East Coast route (SONAR: FBXD.CNAE). Rates are essentially flat year-on-year.

Even if carriers have reduced capacity perfectly in line with lost demand, rates should still be down year-on-year because the cost of fuel is much lower, down 44% year-on-year — and yet, rates are not lower.

Lars Jensen, CEO of Copenhagen-based SeaIntelligence Consulting, highlighted the “remarkable resilience of container freight rates” in an online post, noting that “there is, as yet, not a hint of the lower oil prices undermining the rate levels.” Click for more FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller

Christine Sebek

Lower oil prices are insignificant in the present. Carriers, like most industries dependent on large comsumption of fuel, purchase oil at least a year or more in advance. Therefore, the market bunker prices were significantly higher a year ago when the oil was purchased. Lowering rates to current bunker costs would exacerbate the losses carriers already experience via blank sailings, volume losses and empty equipment repositioning.