PALMER, Texas — Successful autonomous trucking runs have nothing in common. As in nothing happens that the robot driver cannot handle as intended. That includes knowing to slow down for the man who occasionally walks his dog along Interstate 45 south of Dallas.

Aurora Innovation’s autonomous trucks have seen the man and the dog before and the robot Aurora Driver systems learned to brake almost imperceptibly, obeying the Texas law to shift one lane to the left or reduce its speed by 20 mph.

“The Aurora Driver benefits from all of its experiences on both cars and trucks,” said Lia Theodosiou-Pisanelli, Aurora vice president of partner products, programs and operations. “It’s probably seen more pedestrians on the side of the road when operating in cars, but that experience translates to trucks.”

Watching out for anything unusual on the roadside is part of Aurora’s pilot of linehaul logistics for FedEx in conjunction with Paccar Inc., one of its two truck manufacturing partners. The multiple weekly round trips cover about 450 miles on the mostly flat I-45 to Houston and back.

Several times a week, FedEx drops fully loaded trailers at Aurora’s terminal about 27 miles south of Dallas; Peterbilt Model 579 tractors equipped with Aurora Driver take the goods to Houston and return.

The company dressed up its functional buildings along the east side of I-45 for investors and analysts to see in late September. Aurora (NASDAQ: AUR) completed a business combination Nov. 2 with a special purpose acquisition company led by investor and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman. Aurora invited FreightWaves for a tour and ride on a portion of its FedEx route earlier this month.

Similarities and differences

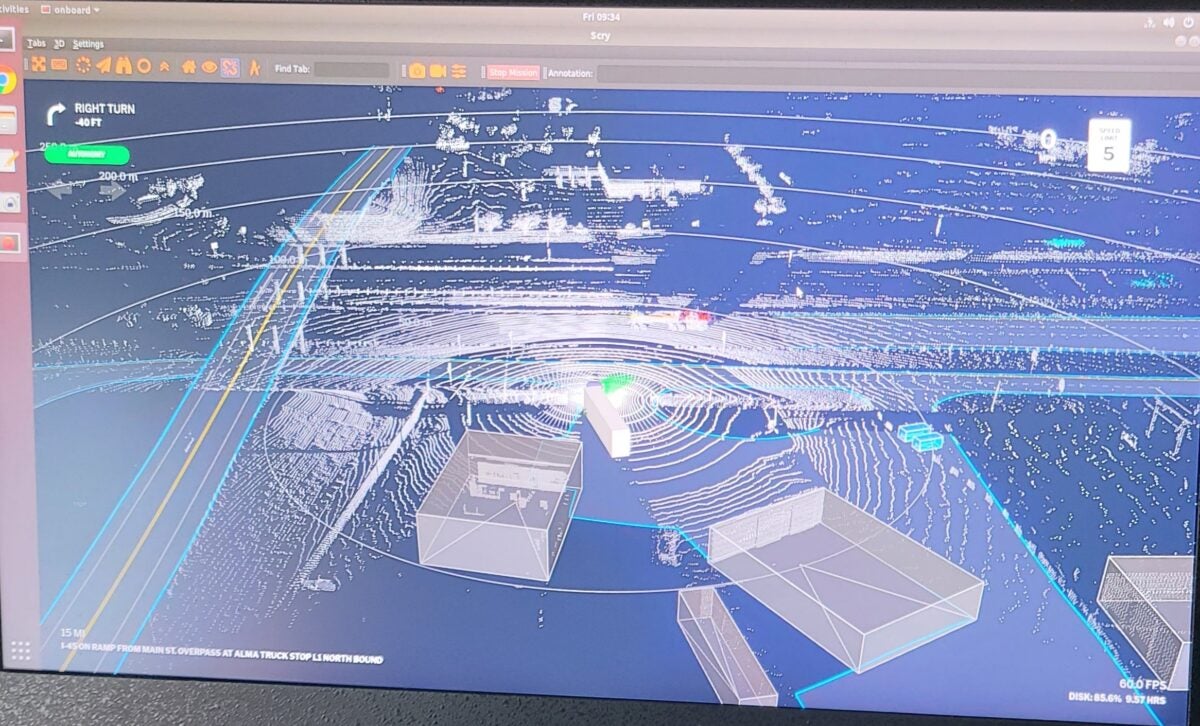

Like earlier competitor-hosted exposures to their autonomous trucks, Aurora used a Model 579 with its sleeper berth converted to hold the “compute” equipment stack and side-by-side rear seats for observers to track the truck’s movements on a computer screen.

While some startups have an engineer accompany a safety driver, Aurora terms its human supervisors as pilot and co-pilot. The co-pilot monitors a screen that sees what the robot sees and checks off with the safety driver as necessary. He also notes anything that would help the robot learn to drive better through the creation of thousands of simulated scenarios.

“Maybe it’s a capability we haven’t developed or some sort of scenario on the road. That event will go to our simulation teams,” said Pisanelli, an economist and former policy analyst before helping build AV capabilities at Lyft, She narrated the 28-mile demonstration.

Compared to recent rides in TuSimple Holdings (NASDAQ: TSP) and Embark Technology (NASDAQ: EMBK) trucks, Aurora had no tricky maneuvers to perform like a highway cloverleaf or driving through a tunnel. The truck operated in autonomous mode on a short course of surface streets — its terminal is on a frontage road next to the interstate — to reach the on-ramp to I-45.

Once on the freight-dense highway used daily by 8,500 conventional trucks moving between the nation’s fourth and ninth most-populous cities, the robot stuck mostly to the right lane, following what Pisanelli called the green carpet projected on the screen. It moved to the center of three lanes when traffic conditions allowed, never exceeding 65 mph.

Pisanelli would not speculate how close the Aurora Driver system — the same system being developed for ride-hailing in Toyota Sienna minivans in 2024 — is to production intent.

“To get to that point of removing the driver, there’s a lot of work that has to be done,” she said. “That’s only one piece of the puzzle.”

Safety framework

Another is to assure itself, its customers and the public that robot trucks are safe. To that end, Aurora in August released its multilayered safety framework, a living document of five claims — proficient, fail-safe, continuously improving, resilient and trustworthy — to support its thesis that its self-driving vehicles are acceptably safe to operate on public roads.

Each of the claims has subclaims backed by evidence made up of test results, peer reviews, audits or assessments. These can change over time as the technology matures.

“We’ve seen competitors talk about safety progress in terms of the number of on-road miles they’ve driven; it’s not the right approach to build a commercially viable product,” Nat Beuse, Aurora vice president of safety, said in a blog post announcing the safety framework.

“Given the complexity of driving and the infinite number of scenarios one might encounter in a given operational domain, this brute force method does not allow a company to adequately amass enough miles to understand the safety performance of a commercial product,” Beuse said.

It would take hundreds of billions of real-world miles, and possibly hundreds of years, to make a reliable safety case in terms of fatalities and injuries.

“Even if this approach did work, once a software or hardware change is made to the technology, there’s no way to confirm safety performance other than to drive those miles all over again, Beuse said.

With about a dozen trucks in its fleet, Aurora “is really intentional about what we do on the road,” Pisanelli said. Take unprotected left turns, for example. Before Aurora tried its first one in the real world, it conducted 2.2 million of them in simulation.

“When we’re hauling loads, we’re also developing [software] at the same time,” she said. “We’re able to have a smaller fleet because so much of our development actually happens in simulation.”

The scorecard to date: 4.5 million real-world miles on roads in California, Pennsylvania and Texas. Billions in its virtual testing suite.

Multiple partnerships

Aurora has worked for several years with Peterbilt, whose 700,000-square-foot manufacturing facility is located a little more than an hour northwest of Palmer in Denton, Texas. Aurora recently received its first redesigned Model 579 to equip with the Aurora Driver. And Paccar CEO Preston Feight dropped by recently to check on progress.

Aurora also has a manufacturing partnership with Volvo Trucks. It is the only autonomous startup with two such OEM arrangements. Both are proceeding at the same pace but work with Paccar (NASDAQ: PCAR) started earlier..

A prototype of the Volvo VNL that will include the Aurora Driver for testing as soon as next year was on display for the analyst visit. Full integration will come on a future version of the VNL, introduced in 1996 and the recipient of multiple upgrades over the years.

The partnership with FedEx is similarly deep, Pisanelli said.

“It’s not just, ‘Hey, we’ll haul loads for you and see how it goes,’ but it’s been a deep engagement with them. We talk about what the future of their network will look like when we do all autonomous runs. People think it’s just as simple as picking up a load and dropping it off. But there’s so much nuance into integrating into logistics networks.”

Trucking leapfrogs ride-hailing

Trucking leapfrogged the timing of autonomous car development at Aurora after the 2019 acquisition of Montana-based Blackmore, a developer of frequency modulated continuous wave (FMCW) light-detecting and ranging.

FMCW emits a low-power and continuous wave compared to other lidars that send out pulses of light outside the visible spectrum and then track how long it takes for each of those pulses to return. As they come back, the direction of, and distance to, whatever those pulses hit are recorded as a point and eventually form a 3D map.

Blackmore’s technology was an aha moment for Aurora co-founder and CEO Chris Urmson.

“I think he always believed that there was the opportunity for trucking,” Pisanelli said. “But there wasn’t any technology out there that could allow us to see far enough with enough precision that gave us confidence that we could offer a safe, trucking product.

“When we acquired Blackmore, we said, ‘OK, we can do this now because we can see 300 meters away.’ We can actually have confidence in this technology.”

‘We don’t want to be a carrier’

With Paccar, FedEx and Volvo in trucking and Toyota in passenger vehicles, Aurora has a full plate. Hence, it does not stray from its mission of building autonomous systems.

“We don’t want to be a carrier,” Pisanelli said. “We don’t want to own the assets. We just want to deliver the service, which is really good for the partnership we have with our customers, because we’re not looking to compete with them. We’re looking to supply them. We are experts in autonomous technology. We’re not going to pretend we’re experts in anything else.”

Keeping the fleet lean is part of Aurora’s business case. Aurora needs Paccar, Volvo and their suppliers to create prescribed components for Aurora Driver to operate systems like propulsion, steering and braking. This redundancy allows the truck to experience a component failure but continue to operate as if a driver could take over when there isn’t one present.

“There’s all of these nuances on integrating with the underlying safety systems of the platform, mechanical integration with the geometries of the vehicle … where’s the right place to be putting the sensors? So we have a full list of requirements,” Pisanelli said.

Integration takes time because there is so much back and forth. Ultimately, the Aurora Driver will be integrated on the assembly line.

“To get to that point of removing the driver, there’s a lot of work that has to be done. That’s only one piece of the puzzle.”

Lia Theodosiou-Pisanelli, Aurora vice president of partner products, programs and operations

“It’s a very symbiotic relationship,” Pisanelli said. “We’re not looking to build a truck. They’re not looking to build an autonomous system. We come in and say, ‘These are the requirements that the platform has to have in order for us to safely integrate our system into it.’ And then they say, ‘OK, in order to maintain our safety or manufacturability, here’s what we can do.’

“It just doesn’t make sense to press print on the early, prototype vehicles. It’s very expensive. You’ll absolutely see our fleet grow, particularly once we have these Peterbilts, we’ll start to have Kenworth, we’ll have Volvo trucks on the road. And then, once we’re able to remove the driver, it’s really a sort of press print and get more vehicles out.”

Ride recap

Pisanelli recapped our uneventful, disengagement-free 45-minute ride.

“We’ve done some lane changes around slow-moving vehicles. We’ve slowed down ourselves because of slow vehicles in front of us, four-way stops, unprotected lefts, merges, but pretty boring.”

Just the way she likes it, even when a guy decides to walk his dog on the side of the busy highway.

Related articles:

Aurora closes in on production version of self-driving truck technology

Aurora, PACCAR and FedEx team up to test autonomous trucks in Texas