East Coast retail diesel prices are soaring relative to the rest of the country, propelled by inventories in the region that are almost half of what they normally should be at this time of year.

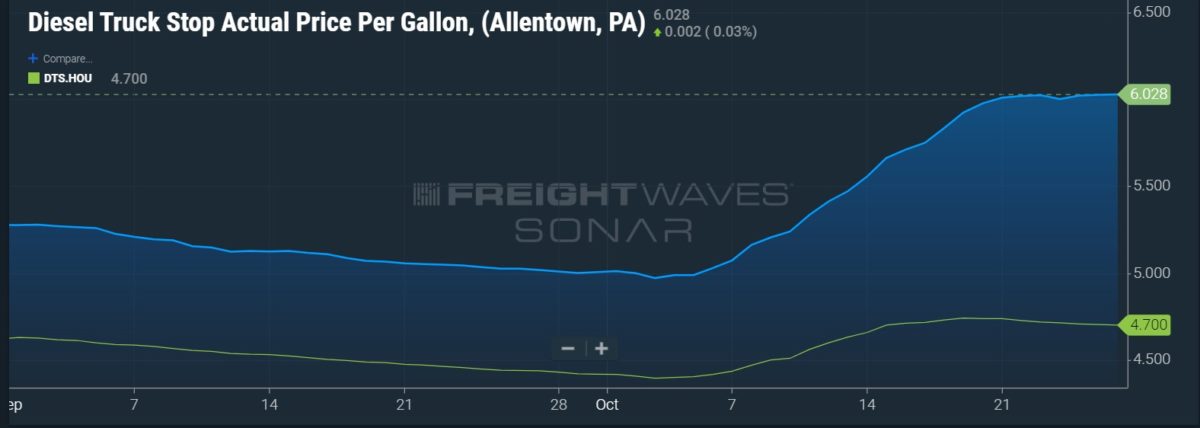

Retail prices recorded in the DTS data series in SONAR tell the story of how much diesel has surged. On Sept. 16, retail diesel in Allentown, Pennsylvania, a major logistics center, was $5.116 a gallon, while the Houston price was $4.513 a gallon, a spread of just over 60 cents. On Oct. 15, Allentown was $5.663 a gallon while Houston was $4.70, a 96.3 cent gap. By Thursday, Allentown was at $6.028 a gallon and Houston was $4.70 a gallon, a spread of $1.328 a gallon.

The East Coast price blowout has been propelled largely by the tight inventory situation in what is known as PADD 1, the Department of Energy’s designation for that region.

Weekly statistical data reported by the EIA this week had PADD 1 inventories of ultra low sulfur diesel at 21.3 million barrels for the week ended Oct. 21, a more than 7% decline in just one week. But more striking was the fact that those inventories are 56.5% of the five-year average for the corresponding October weeks, excluding the pandemic-influenced data from 2020.

By contrast, national inventories for all distillates, which are not broken down by specific grades, are running about 80-81% of the five-year average, and that is considered extremely tight by analysts.

Tight supplies on the East Coast were also driven home this week by a Supply Alert published by Mansfield Oil Co., a leading supplier of wholesale fuels to the East Coast and other parts of the country.

Mansfield, in a Supply Alert published Tuesday, said it was moving to a Level 4 alert on diesel supplies. It was not immediately clear what happens at Level 4, though it is less severe than the Level 5 alert it had implemented for Hurricane Ian. An email sent to Mansfield had not been responded to at publication time.

The Supply Alert also said it was moving the Southeast region to Code Red. Under Code Red, the company is requesting a “72 hour notice for deliveries when possible to ensure fuel and freight can be secured at economical levels.” The step below that, which was implemented for parts of the country during Ian, is Code Orange, requesting a 48-hour window.

The data on the East Coast supply squeeze is visible in other indicators. For example, data provided to FreightWaves by a third party shows that the spread between Brent crude and ultra low sulfur diesel delivered via pipeline in Linden, New Jersey, published by S&P Global Commodity Insights, which houses its Platts operations, recently has been near $85 to $87 per barrel. But that is down from just a week ago when it broke past $100 for three consecutive days. A month ago, it was around $50 a barrel.

Other price data, befitting a market in such turmoil, is all over the place. For example, Pilot Flying J publishes a downloadable spreadsheet of the retail prices throughout the entire 830-plus outlet system. And while prices there do show the East Coast significantly higher than the Gulf Coast, the spreads are hardly consistent.

For example, as of Friday morning, the Pilot Flying J outlet in Pasadena, Texas, a Houston suburb, was showing a price of $5.199 a gallon. But in Staunton, Virginia, along Interstate 81, a key north-south route on the East Coast, prices were only 20 cents more than that. Head on up 81 a little farther to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and a gallon of diesel would put you back almost $6.40.

The weekly Energy Information Administration data is showing little difference between the East Coast and the full country, just $5.341 a gallon nationally versus $5.379 a gallon on the East Coast, as of Monday. The East Coast numbers are embedded in the national number.

But the spread with the Gulf Coast most recently was 39.2 cents a gallon, with the Gulf still below $5 at $4.987 a gallon. That almost 40-cent spread isn’t even the highest this year; it was well over 60 cents during a similar East Coast squeeze in May.

With those kinds of margins, East Coast refiners — a dwindling breed — are rushing to take advantage of it — those that are left.

PADD 1 refiners ran at 102.5% of capacity in the week ended Oct. 21, the EIA said, a statistical quirk as refiners find ways to exceed their nameplate capacity. However, it is generally viewed as not sustainable for lengthy periods of time.

But that 100%-plus rate is just recent; normal levels of fall maintenance pushed that utilization rate between 85% and 90% for five weeks beginning in mid-September.

It is also against a base capacity estimated by the EIA of 818,000 barrels per day, down from 1.22 million barrels a day through mid-2020. But the region has been hit with several refinery closures in recent years, the most notable being the giant Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery, which closed several months after a 2019 fire. That took 335,000 barrels a day of refining capacity off the East Coast market.

Not counted in the EIA figures for the East Coast is the closure of the Come-by-Chance refinery in Canada’s Newfoundland province in 2020. It is being replaced by a renewable diesel facility that will produce 18,000 barrels a day of that product, which can be consumed in diesel engines without any further processing. But if the 133,000 barrels a day refinery produced one-third diesel, which is a rough estimate for most refineries, that’s still a loss of almost 30,000 barrels a day of diesel supply on the East Coast.

The facility to replace Come-by-Chance is called Braya Renewable Fuels, and it isn’t in commercial operation yet.

The irony in the tight market is that there are some signs of declining demand. The EIA’s most recent figure for Product Supplied, its proxy for demand, showed all distillate consumption in the week ending Oct. 21 at 3.87 million barrels a day. That is the first week less than 4 million barrels a day in four weeks, though demand had been less than that 4 million figure for 24 out of 25 weeks prior to that.

But EIA data generally has the third week of October in excess of 4 million barrels a day, as it comes in the middle of harvest season and consumers who use heating oil filling their tanks in anticipation of winter. Heating oil, like diesel, is a distillate and weekly data does not break down different types of fuel in the Product Supplied number.

More articles by John Kingston

Used truck prices help Ryder year-on-year but declines cloud forecast

XPO brokerage spinoff RXO gets near-investment grade debt rating from S&P

DOL independent contractor definition could pose problems for truck fleets

Performance record

Feds have Foreign People working as FBI agent’s to get company driver jobs then pick up a load before the driver that was assigned to the load like double dispatching then take it to the Canadian border and leave it for some zing to pick up

Carlos_P

Gov Wolfe’s Democrat Ruled Pennsylvania is the highest in the country right now at $6.39/gal in Harrisburg PA. (Former Keystone XL pipeline)