“It was the best of times; it was the worst of times,” – Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

Had Charles Dickens been a trucker in 2019, it would have been highly likely that he would have truncated this famous sentence to “It was the worst of times.” The freight recession that started in early 2019 has unfortunately continued, and for many has gotten worse. Profits have been almost non-existent for carriers of all sizes, and for a large portion of the carrier population, the entire year of business ended with absolutely nothing to show for it, not to mention cash injections from owners.

A dollar invested in any business should be worth more at the end of the year than at the beginning. That’s the whole point: to make money. The average North American motor carrier generated a negative return on its assets in 2019. That dollar invested at the beginning of the year was worth less, not more at the end of 12 months. For the average reader, without an education on the economics of trucking, the response to this statement would simply be that this is the risk of being in business: you take the good years, you take the bad years, and on balance, if you do the right things, you earn a profit. However, the problem with trucking is that there are two things to consider: the average long-term operating margins as a carrier (razor thin), as well as the massive risks faced by today’s carriers. Most industry articles typically focus on one or the other, but when you combine the two – rewards and risk – it presents a paradox. Why accept this level of risk for such paltry returns?

The reality is that trucking, like many other businesses (e.g. real estate), is leverage-friendly. It is very easy (over the long-term, not necessarily lately) to obtain credit to grow your business. Banks and lenders like physical assets; trucks are physical assets. This fact doesn’t guarantee success. Unlike some leverage-friendly businesses, trucking does not have a finite capacity. As a result, when times are good, capacity (trucks) enters the market. Incumbent carriers are just as guilty (if not more guilty) for the capacity problem.

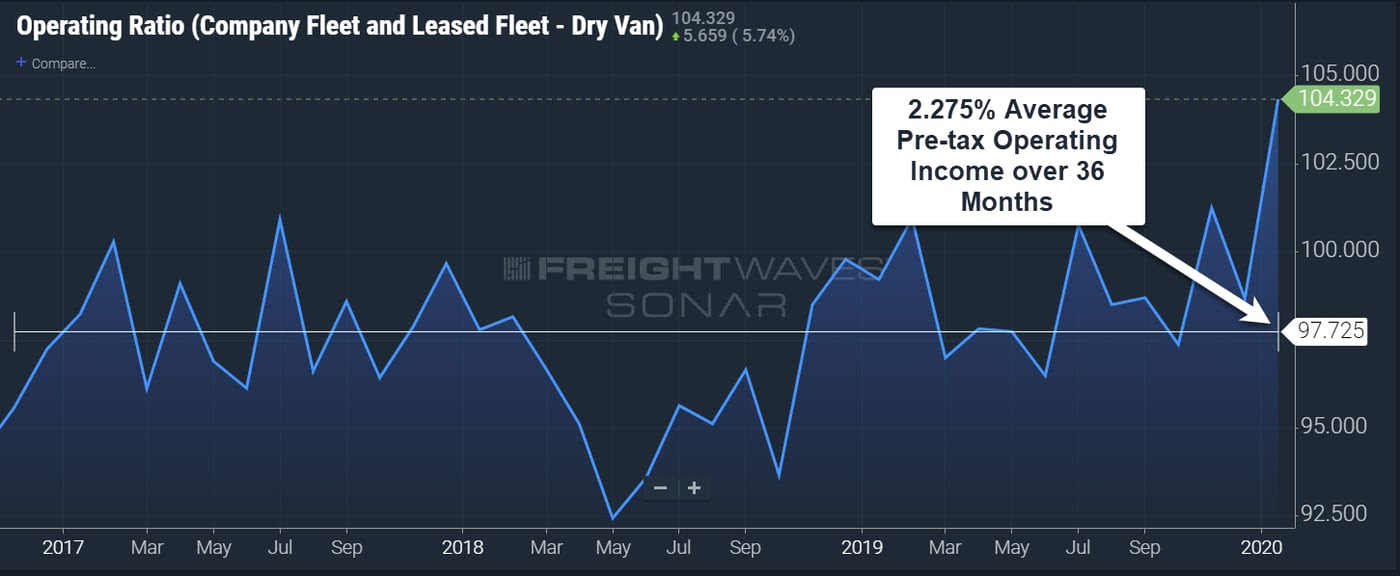

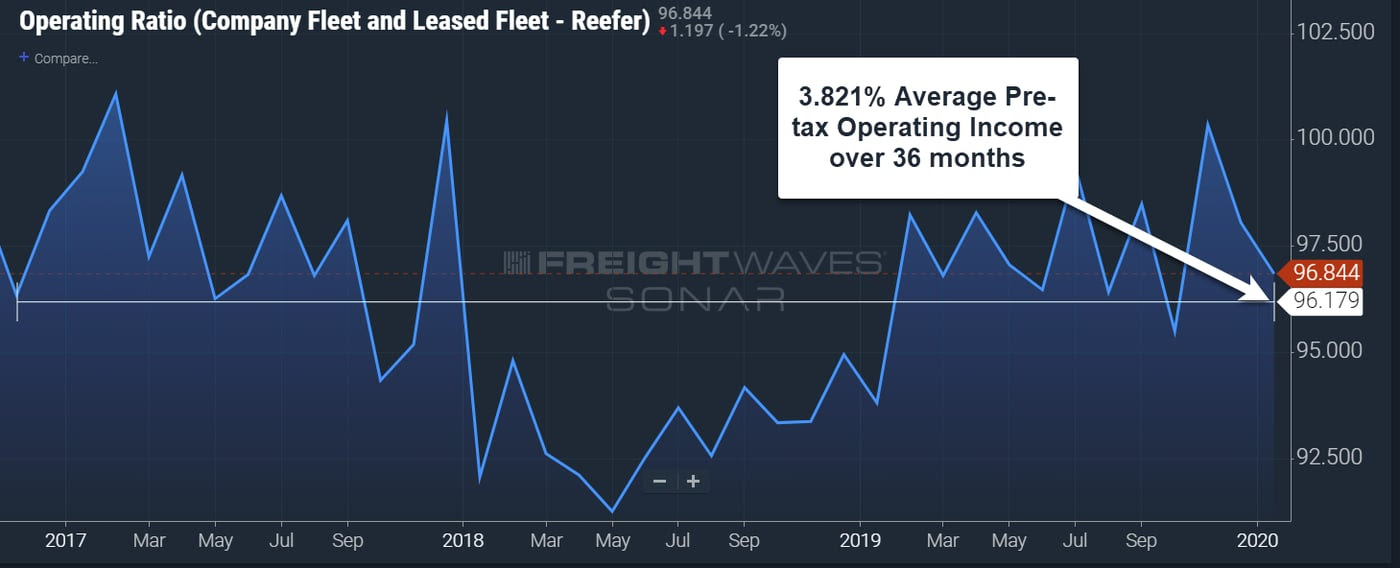

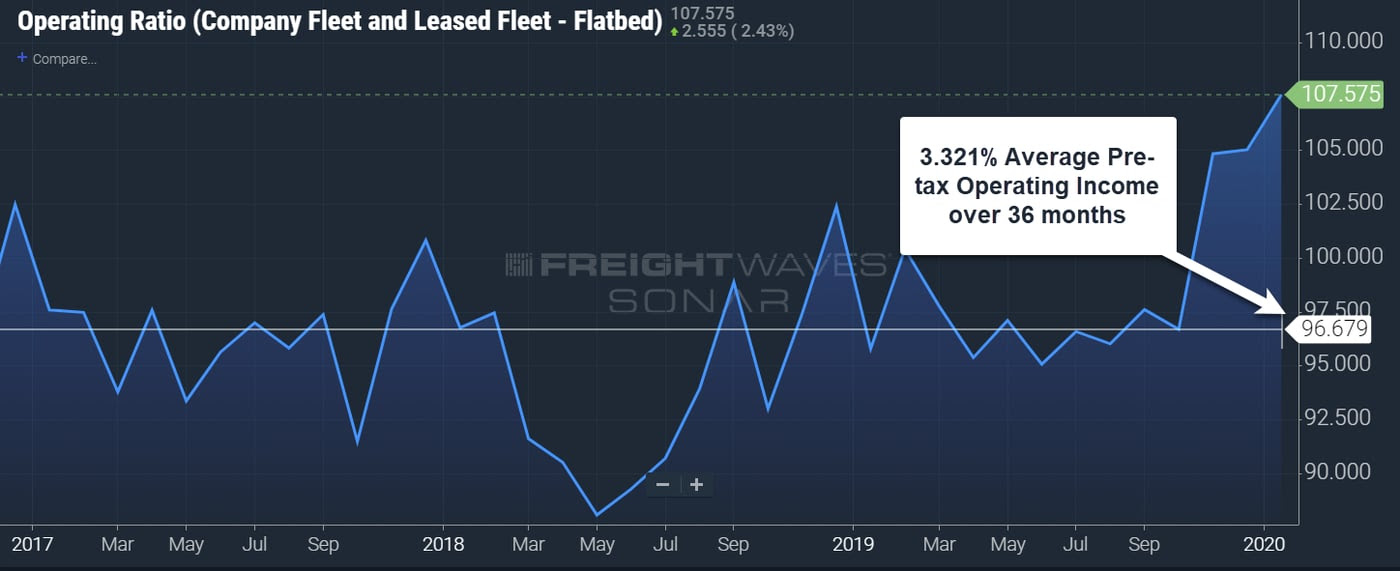

This added capacity causes diminishing returns, even if it temporarily provides an increase in absolute profits for a carrier. The charts below illustrate, using empirical data, what the roller coaster of trucking profitability looks like.

The underlying data is gleaned from participants in the TCA Profitability Program (TPP), which is comprised of 238 trucking company profiles, of all sizes and modes, throughout North America. Although we do not have empirical data to confirm our hypothesis, we believe that the profit margins for the wider trucking community were significantly worse than described below. If that is correct, this is the best case. For those in the shipper community that are reading this, this is what transportation looks like on this side, this is the main street of trucking. For every Heartland Express, there are tens of thousands of ACME carriers that have done worse than the averages described below.

Source: FreightWaves SONAR

Source: FreightWaves SONAR

Source: FreightWaves SONAR

Now, let’s consider the risk side of the equation. For many, the first thing that comes to mind is the rising tide of litigation, and the number of nuclear verdicts being imposed on the industry. This is a trend of great concern. Carriers of all sizes and safety profiles are finding themselves on the wrong side of jury decisions at a growing rate. A decade of earnings can evaporate for both carriers and insurance companies with these kinds of judgements. When you combine these potential judgements with the difficult freight environment, most companies simply do not have the resources to assume liabilities from nuclear verdicts – or any jury verdict at all.

Nuclear verdicts, rising insurance rates, depressed used truck pricing, difficult macro and micro economics and countless other curve balls make it very difficult for a pragmatic business person to justify being a trucker. However, this is where the doom and gloom ends, and opportunities start.

Financial and operational literacy

After being part of the TCA Profitability Program for five years, I’ve been provided with the unique opportunity to observe, first-hand, the inner workings of a growing number of trucking companies, and gain insight from the leaders in each of those businesses. From this experience, I believe (you be the judge) I’ve been able to distill some of the traits of those companies that have achieved significantly better returns (profits) than the average carrier. Many of these top-performing companies had their best years in 2019! These traits are part of a common theme; these companies have treated the diseases that cause low returns, not just the symptoms.

The most viral disease in trucking is a lack of financial and operational literacy in this industry. All of today’s top trucking companies started with one truck. Trucking entrepreneurs are problem-solvers, and many have succeeded simply because they have the ability to put out fires rapidly, and sheer willpower to make some money along the way. However, once you start building a team, it can prove difficult to provide an education on the financial and operational realities of trucking – they are typically too busy putting out fires to take a step back, to identify a better way. A common trait among top-performing carriers is that they are very transparent in their operational and financial results, and are able to communicate these results in a way that anyone can comprehend. This, tied with line-item accountability and merit-based compensation, is a formula for success.

How does one start the journey towards both transparency and education? The first step is to eliminate metrics that many have difficulty understanding. At the top of the list is operating ratio (OR). I’ve had countless conversations with CFOs, new to the industry, who didn’t quite fully understand the components of an OR. The reason is that it’s not part of the normal language of businesses. Only three industries that I can think of use OR to communicate financial performance, as a default measure – trucking, railroads and insurance. Almost all other industries focus their attention on the inverse, operating income, as a percentage of revenue, and return on assets. If a CFO is asking what an OR is, it is highly likely that the vast majority of people in the company don’t know either. Operating ratio is also a subtle cloak for a stark fact – returns suck. To the average reader, what is more alarming, a 98.5% OR, or 1.5% operating income (or a 101.5% OR compared to -1.5%). I think the answer is clear.

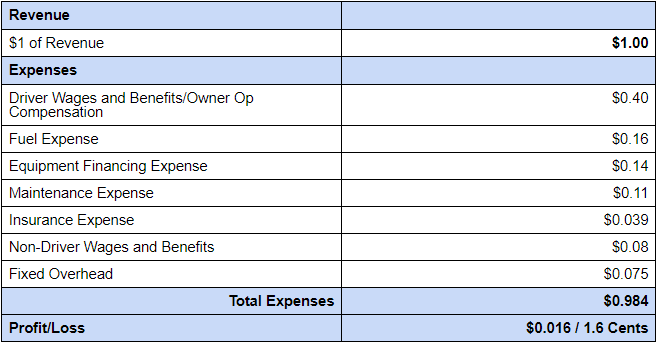

Taking this one step further is translating the economics of trucking into a format that reinforces the challenges (and opportunities) in trucking in the language of business. One great method, which I feel very strongly about, is providing employees with a simplified profit and loss (P&L) statement. An example of this, which is available for all TPP members, is a P&L format using $1 of revenue as a starting point.

Using the above example, for every dollar of revenue generated, the carrier has kept just 1.6 cents. If you were to survey your employees using the standard question “For every $1 of revenue, how much (after all expenses) do we keep, in the form of profits?”, it would be a safe bet that the average response is going to be much greater than 1.6 cents (or 1.6% operating income). If your employees don’t know the stark realities of trucking, there is very little opportunity to influence front-line behavior, and daily decisions. If the employee believes that the company is keeping 30 cents on every dollar, it’s another safe bet to assume that he or she is rationalizing decisions that may have cost the business substantial sums.

This ties into the second trait of top-performing companies, which is really a timeless mantra.

A penny saved is a penny earned

Achieving larger relative rates per mile compared to the competition is extremely difficult. This is due to the fact that the trucking market is extremely efficient because of its pro-competitive aspects. As a result, shippers shouldn’t have any fears whether they are receiving the best possible price, within any given market. Instead of chasing top-line dollars, the best performers continually reinforce to their teams that every penny saved flows directly to the bottom line in the form of profit. This is a much better strategy than simply deciding to go after profit by adding more revenue (a strategy which is the underlying disease in trucking). Heartland Express, as a notable example, is widely known as a company that employs this strategy with great success (net margins of 25+%). This strategy can be distilled into a mantra that more carriers should repeat – Margin Before Truck Count. However, just talking about saving money is not the answer. People, the foundation of all businesses, need to take responsibility and be held accountable for the things they control.

Accountability and WIFM

Closing out the ‘top traits’ is accountability and merit-based compensation (WIFM – what’s in it for me). These are the final pieces of the puzzle that can eliminate the disease of market-level profitability in a trucking company (or any company). Once a team member can fully grasp the language of business (the financials) and the economics of trucking, only then will they be able to fully grasp both the implications of their role and tasks. It’s only natural, once armed with the data and education, for people to want to improve. A common method to expedite the improvement is to connect accountability for expenses and strategies with compensation, whether direct (bonuses) or indirect (trips, gift cards, company events, etc.).

In summary, top performers not only arm their employees (from the driver seat to the C-suite) with information on the health of the company, they also provide that information in a format that can be understood by anyone. These companies reinforce the importance of cost containment and discipline with respect to capital and time-consuming investment. Finally, they decide who (individual or group) is going to be held responsible for maintaining that discipline. In the end, if the formula works for your company, it will result in a more profitable enterprise, and eliminate the behaviors and people that have the opposite effect. You have treated the disease, instead of the symptom. Margin before truck count.

Jerry Noonan

I am not sure where the source of Chris’s numbers. I have been doing transport cost accounting segmenting for some 40 plus years. One needs to fully understand cost/volume/profit relationships to keep a transport carrier, small or large, in business. Interstate trucking remains a federally regulated utility. To provide a mile of transport service every transport carrier has production costs that require a per mile revenue requirement. Like any other utility. Since rate deregulation 40 years ago, total truckload transport production costs have increased at approximately the rate of inflation. Further since the amount of miles driven are regulated an owner operator with one semi-truck will generally run approximately 100,000 miles annually depending on what part of the country operated in.

Knowing transport margins, dollars remaining after variable line haul costs, is essential to cover remaining fixed, shop, and general and administrative costs. Like in regulated days a profit costs should be added to costs. If you don’t know your transport margins (not the same as an operating ratio), a transport carrier has little chance of reaching a fair and reasonable return on invested capital.

Here would be a reasonable targeted revenue requirement for a Midwestern owner-operator running approximately 100,000 miles per year.

Revenue Requirement $ 2.1986 per mile

Current Diesel Fuel costs $ .4337 ”

Driver wages, taxes and fringe benefits $ .7564 ”

Other over-the-road variable costs $ .0572 ”

Fixed Costs, (interest, depr. licenses, insurance, etc.) $ .5956 ”

Shop and maintenance Costs $ .1338 ”

General and Administrative Costs $ .1219 ”

Profit Costs $ .1000 ”

There is an old saying in truck costing, “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will take you.” To many transport carriers don’t know their revenue requirements and don’t know where they are going.

A Driver

Rule # 1 no driver in the cab, no spinning wheels to deliver the freight.

Drivers who leave their homes, families and children to earn a living need to be paid accordingly, cheap freight hits the trucking companies, because they loose drivers and eventually is no one who is willing to sacrifice so much for so little.

You get what you pay for, cheap rate might seem good for the customer or the broker (who ripped a carrier off at the right time), but gets a less maintained truck/trailer, less experienced driver and so on… People with experience know their price tag and they care less if you hang up the phone on them and don’t want to negotiate a better price, because experienced drivers don’t want to deal with idiots either.

Rule# 2 DETENTION has to be paid. This doesn’t show in the reports and all we read is bla-bla-bla about $/mile

While with such strict ELD in place, time=$

So I can care less if it is 300 miles trip, if it takes a day to deliver it has to pay for that day the driver the insurance, fuel, office…

700 Miles is 2 days transit with loading and unloading, ain’t just $/mile anymore.

When someone say I covered for cheap, i reply: “Glad for you” And I mean in, good that someone made money and good that someone without insight will go bankrupt soon, it’s bringing less competition in the long run for us.

Be smart and make correct decisions. The freight will not teleport itself, it won’t go anywhere without drivers for very long time.

You tell your price, not someone shall tell you what you shall get for risking your life and sacrificing time with your family.

Hans Witt

Well here is what Chris said in a nut shell. 1 cheap interest rates has causes to much capacity, that is true to some degree. 2 Chris can produce a lot of statistics and use them to support his article! “They” have always done this. I would like to see someone to flourish and be profitable with $97’000 per year, paying them selves .40 cents a mile. As a general rule the the phoney statistics they publish to entice naive people to become owner operator are about 100% below what it really takes to run a truck. The above figures were used 20 years ago , Rates are the same story they were 20 years ago to. They have went up a little, but not much, what has changed is information technology, allowing independents access to freight. I say people writing propaganda from the top-down prospective , using big words to re write same old story. #3 Same old story is this_ The carrier & driver are to assume all risk & accountability, while hauling for what ever rate the broker & shipper doles it out for. They are to do this with a $140000 power unit, $ 50,000 driver, 15000 insurance, $3.25 fuel, over bearing HOS & ELD that reduced productivity 15%, Maintenance is at least .30 cent mile Chris, if your lucky, WE are all to do all this with the same rates we got 20 years ago, right Chris. I say article such as your this put to many truck on the road too!, along with no regulation of brokers, factoring companies, and illegal immigration. I bet this this just to much